Playing detective with Canada’s female literary past

By Carole Gerson, Professor, English Department, Simon Fraser University

From left to right: Lotta Dempsey, Alice Evelyn Wilson, Elsie Gregory MacGill, Katharine Emma Maltwood and Elise Aylen Scott

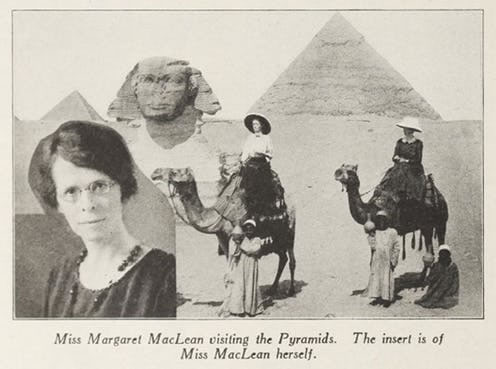

Margaret MacLean visited and wrote about the Royal Ontario museum’s collections as well as visiting Egypt for Saturday Night magazine. (Database of Canadian Women Writers)

Most Canadians know surprisingly little of their country’s literary past, even though many of their great-grandmothers or great-aunts were active participants in Canada’s print culture as poets, journalists, novelists, travel writers and biographers.

While Canadians like to believe their country has produced an extraordinary number of fine women writers, when we look closely, the number of recognized female authors included in influential areas such as anthologies for university courses, nationally focused reprint series and commemorative activities is low—far less than 50%.

However, over the course of the last two and a half centuries, surprisingly large numbers of relatively obscure women got their writings into print—in different genres and on different topics—in magazines, newspapers, anthologies, chapbooks and full-length volumes, even though few would achieve renown or receive attention from scholars.

My research on early Canadian women writers has resulted in the collection of thousands of names, which now appear in the recently launched Database of Canada’s Early Women Writers (DoCEWW). This resource includes Canadian women writing in English whose first publication appeared in or before 1950. It was created with support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), the Simon Fraser University Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, the Department of English and the Digital Humanities Innovation Lab at SFU.

Database of early Canadian women writers

Sarah Jameson Craig is a Canadian writer discovered by her great-grandaughter. McGill-Queen’s University Press

Some writers, such as Sarah Jameson Craig, were brought out of the shadows by family members—in this case by her great-granddaughter, Prof. Joanne Findon.

While writing was not a major focus of Craig’s life, her various activities as a feminist, health reformer and utopian thinker were, at times, expressed in print.

Craig exemplifies the majority of the writers included in the DoCEWW.

Alongside a smattering of well-known professional authors and journalists such as Lucy Maud Montgomery, Nellie McClung and E. Cora Hind, the database includes some 4,800 Canadian women who published their words occasionally—as manifestations of their interests, professional activities, ideology or creativity as they got on with their busy lives.

In addition to poetry and stories for children, their writing ranged from pragmatic concerns such as agriculture or knitting, to professional topics or the history of their family or community.

For each writer, DoCEWW provides basic biographical and publication details including names (primary and alternative), places and dates of birth and death, places of residence, titles of books and other publication venues like anthologies and serials.

Naming women writers

Confirming the various names used by women writers can pose quite a challenge because, historically, women have changed their names after getting married and because many women writers used pen names.

In DoCEWW, the author’s primary name is the name that she was best known by, with all her other names listed as alternatives.

For example, the primary name of the woman who wrote Anne of Green Gables appears as L.M. Montgomery, the name under which most of her work was published. Her alternative names include her full birth name (Lucy Maud Montgomery), her married name (Mrs. Ewan MacDonald) and the various pen names she used, mostly at the beginning of her career: Belinda Bluegrass, Cynthia, Joyce Cavendish, Maud Cavendish and J.C. Neville.

Working with a team of excellent student assistants under the expert direction of project manager Karyn Huenemann, we have done our best to disentangle writers who share the same name, such as the two women who published as Mary Agnes Fitzgibbon. One was a granddaughter of pioneer author Susanna Moodie, while the other was a rather flamboyant journalist, Mary Agnes Bernard, who became Fitzgibbon upon marriage.

Finding women writers

Many of the women in this database did not present their writing in separate volumes or chapbooks, but were published in periodicals or anthologies. These two formats are a critical component of Canada’s cultural history.

Database users can track down writers whose names they might find in such newspapers, magazines or anthologies (of which there have been surprisingly many). In this way, researchers can use the database to explore historical publishing practices.

A click on a writer’s name brings up all the titles with which she is associated, and a click on the title of a periodical or anthology brings up the names of all other contributors who appear in the database.

Pioneer paleontologist Madeleine Fritz at work. (Database of Canadian Women Writers), Author provided

It’s one thing to collect the names of obscure female authors and quite another to pin down who these people actually were. While much can be gleaned through such on-line resources as Ancestry, we have also depended on the knowledge of many others, including librarians, archivists and other custodians of cultural materials, as well as relatives and descendants of writers, and friends and acquaintances who informed us about publications or CBC programs.

For example, a visit to the library and archives of the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) identified a cluster of female authors not yet on our list.

These writers had engaged in a range of activities that illustrate women’s multifaceted connections with print: Pioneer paleontologist Madeleine Fritz published scholarly research; in 1917, Margaret MacLean, the museum’s first official guide, published educational articles about the ROM’s collections in Saturday Night magazine; classicist Cornelia Harcum published a book about Roman cuisine in 1914 and articles about the ROM’s classical collections in the 1920s; and the extensive careers of Katherine Maw Brett and Dorothy K. Burnham in the ROM’s textile department began with Brett’s 1945 exhibition pamphlet and Burnham’s first book, published in 1950.

Discovering the stories

Serendipity has played a role in identifying many writers now in DoCEWW:

Mary Elizabeth (Connell) Donaldson

Seeing one of Elizabeth Donaldson’s poems on our website, two of her great-nephews asked project manager Karyn Huenemann which of the Mary Elizabeth Donaldsons in their family tree was the poet. Together they solved the mystery and discovered even more poems in old journals. As the author’s granddaughter was looking for a place to donate her grandmother’s papers, we put the family in contact with the archivist at York University.

Amy Clare Giffin

In 1986, the couple who bought the Giffin family home in Isaac’s Harbour, N.S., found her name carved by her childish hand in the glass of many windows as well as a box of writing and ephemera in the attic. Their research led them to our website. Together we learned more of Giffin’s life, but there are still gaps in the biography.

Jane Layhew

Coral Ann Howells at the University of Reading wanted to determine the relationship between Jane Layhew, a nurse from Prince George, B.C., and a Jane Layhew of Montréal, author of Rx for Murder (Lippincott, 1946).

The back and forth exchange of information created a rich understanding of the life of this one-book author, whose husband, Lew Layhew, was a cousin of literary critic Northrop Frye.

Playing detective

While we have resolved many pseudonyms, mysteries still abound.

Who was the unnamed “lady” who had done much research on the Canadian north and issued A Peep at the Esquimaux in London in 1825?

Did Benedictine Wiseman, the eccentric mother of Mavis Gallant, really publish a play as she claimed to have done while still a teenager?

Will we ever identify the woman who sent an undated letter (likely around 1918) to Prof. Archibald MacMechan at Dalhousie University, asking for his opinion of her published collection of poems, and signed herself as “Mrs. Nobody” of “No. 0 Nowhere Street?”

The investigation continues.

Carole Gerson receives funding from SSHRC, and at Simon Fraser University from the Digital Humanities Innovation Lab (DHIL), the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, and the English Department. This article was originally posted on the Conversation.