Evaluation of the Canada First Research Excellence Program (CFREF)

The Honourable François-Philippe Champagne, P.C., M.P.

Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada,

represented by the Minister of Industry, 2021

Cat. No. CR1-18E-PDF

ISSN 2563-9382

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 The relevance of CFREF

- 3.0 The implementation of CFREF grants

- 4.0 CFREF participants

- 5.0 Partnerships, collaborations and infrastructure

- 6.0 Program design, delivery and cost-efficiency

- 7.0 Conclusions and recommendations

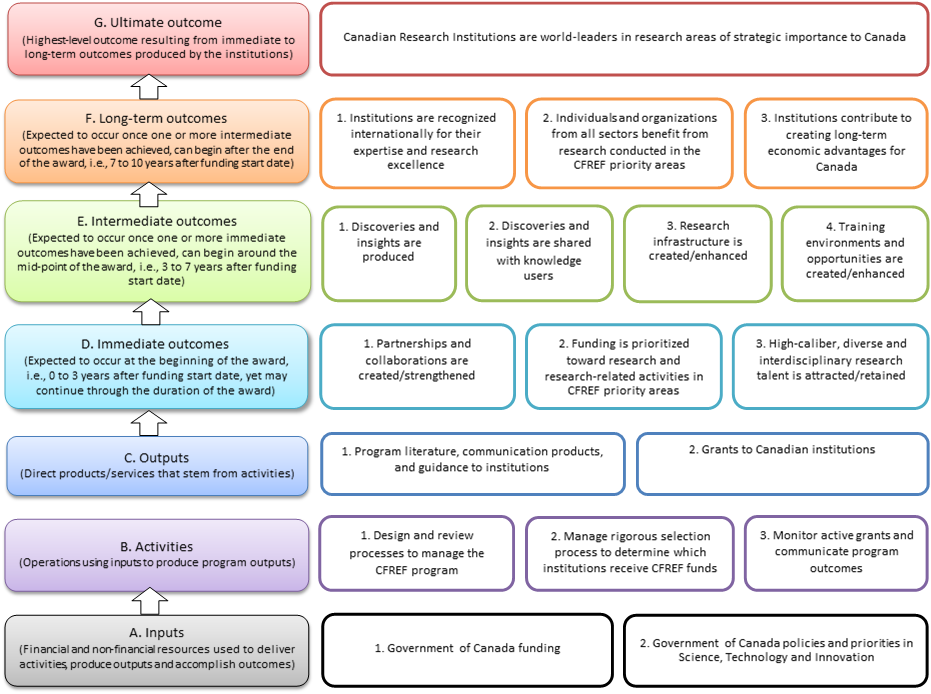

- Appendix A – CFREF Logic Model

- Appendix B – Evaluation Methodology

- Appendix C – References

List of Acronyms

- CAUT – Canadian Association of University Teachers

- CERC – Canada Excellence Research Chairs

- CFI – Canada Foundation for Innovation

- CFREF – Canada First Research Excellence Fund

- CIHR – Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- CRC – Canada Research Chair

- ECR – Early career researchers

- EDI – Equity, diversity and inclusion

- HQP – Highly qualified personnel

- ISED – Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

- LOI – Letter of Intent

- NCE – Networks of Centres of Excellence

- NFRF – New Frontiers in Research Fund

- NSERC – Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada

- PMP – Performance Measurement Plan

- PSIS – Postsecondary Student Information System

- R&D – Research and development

- SPFR – Survey of Postsecondary Faculty and Researchers

- SSHRC – Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada

- STEM – Science, technology, engineering and mathematics

- TIPS – Tri-agency Institutional Programs Secretariat

- UCASS – University and College Academic Staff System

List of Tables

- Table 1. Distribution of CFREF applicants and recipients by size of host institution for the first and second CFREF competitions

- Table 2. Aggregate seven-year projections and actual cumulative expenditures as of 2018-19 for both Competition 1 and Competition 2 (n=18)

- Table 3. Detailed breakdown of seven-year projections and actual cumulative expenditures of CFREF funds for compensation-related expenses (salaries and stipends, including benefits), as of 2018-19 for Competition 1 grantees

- Table 4. Level of funding and distribution of partners by sector and location, as of March 2019

- Table 5. Distribution of participants among Competition 1 and Competition 2 CFREF grants from 2015 to 2019

- Table 6. Distribution of new faculty recruited by Competition 1 institutions

- Table 7. Distribution of new HQP recruited by Competition 1 institutions

- Table 8. Distribution of partners among CFREF-funded institutions

- Table 9. Distribution of collaborators among CFREF-funded institutions

- Table 10. CFREF program-level operating expenditure and efficiency ratios

List of Figures

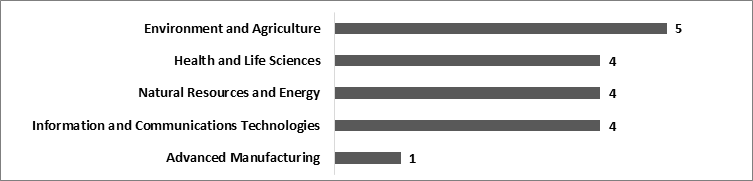

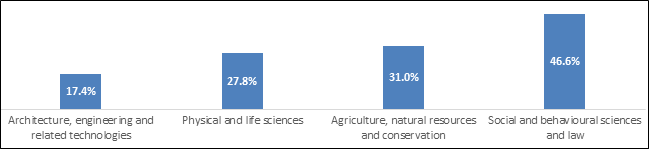

- Figure 1: Distribution of CFREF grants (competitions 1 and 2) based on their predominant priority research area

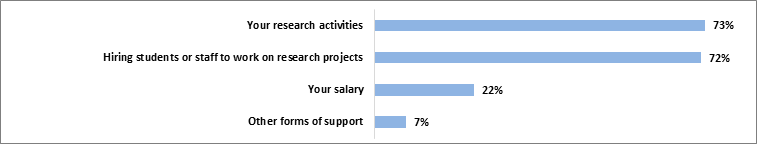

- Figure 2: Range of financial support provided to faculty members involved in CFREF grants

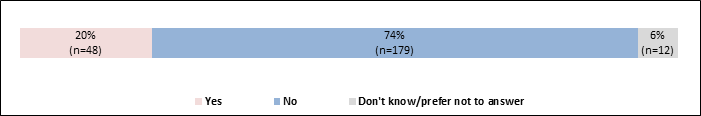

- Figure 3: The proportion of CFREF researchers (n=239) who expressed concerns about the level of satisfaction with the competitive process used to allocate research funds

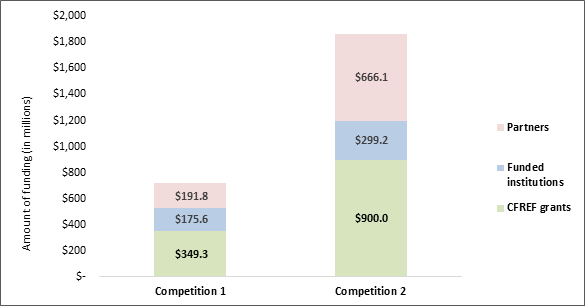

- Figure 4: CFREF funding and leveraged support committed by the funded institutions and their partners for the seven-year grant period (as of the end of the 2018-19 fiscal year)

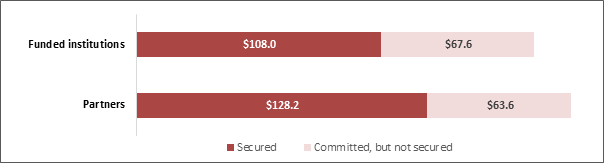

- Figure 5: Competition 1 leveraged funding secured and not yet secured from lead institutions and partners, based on their total commitment for the seven-year grant period, as of March 2019 ($ million)

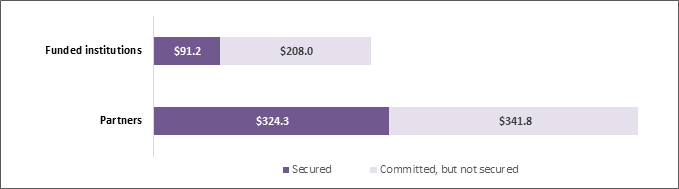

- Figure 6: Competition 2 leveraged funding secured and not yet secured from funded institutions and partners, based on their total commitment for the seven-year grant period, as of March 2019 ($ million)

- Figure 7: Funding awarded by granting agencies to Competition 1 institutions from the time of drafting the proposal until the mid-term of the grant ($ million)

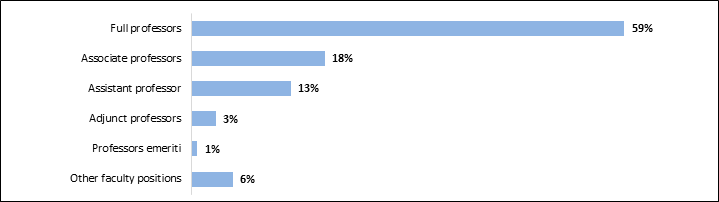

- Figure 8: Type/role of faculty members involved in Competition 1 grants (N=431)

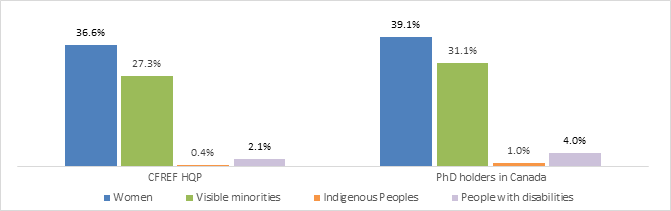

- Figure 9: Comparison of the representation of the four designated groups among CFREF participants with the representation of the four designated groups in Canada’s overall population and Canada’s labour market

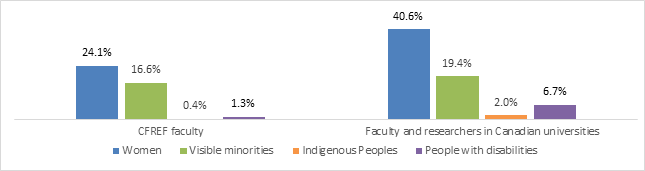

- Figure 10: Representation of individuals from the four designated groups among CFREF faculty compared to full-time professors in Canadian universities

- Figure 11: Representation of women among full-time faculty at Canadian universities by subject area

- Figure 12: Comparison of the representation of the four designated groups among CFREF HQP and the postsecondary sector in Canada

- Figure 13: Distribution of partners by sector, as of March 2019

- Figure 14: Distribution of collaborators by sector

Executive Summary

As the program was launched in 2014, this constitutes the first evaluation of CFREF and covers its initial four fiscal years of operations, from 2015-16 to 2018-19. The primary purpose of the evaluation was to provide an assessment of the relevance and performance of the CFREF program, as well as aspects of design and delivery. The evaluation had a particular focus on immediate outcomes of the first five grants awarded, as it was conducted four years into the delivery of the CFREF program; as such, it was too early to assess intermediate and longer-term outcomes and impacts of these grants and for the program as a whole. Similarly, it was too early to assess longer-term expected results of investing at the institutional level, or to conclude if the program’s focus on funding at the institutional level confers specific advantages or disadvantages compared to funding at the researcher or project level. Nevertheless, based on the information collected, the funded grants have largely met immediate outcomes and demonstrated progress towards achieving intermediate outcomes.

The evaluation involved multiple lines of evidence, including reviews of program documents, relevant literature, and CFREF administrative data (comprising annual progress, mid-term and financial reports from all grantees, as well as the final results of the mid-term peer-review for the five Competition 1 grantees), case studies with the five Competition 1 grantees, interviews with key informants and a web-based survey of CFREF core team members from all 18 grants. The methodology for this evaluation presented some limitations, but these limitations did not prevent the evaluation questions from being adequately addressed.

Relevance of the CFREF program and alignment with government priorities

CFREF occupies a unique niche in the Canadian funding landscape as it is the only large-scale funding program that is designed to support the implementation of scientific and institutional strategies that allow grantees to strengthen their institutional position in a specific field of research. The evaluation concludes that CFREF continues to be relevant, as it provides the government with a unique vehicle for strategically investing in priority research areas which have the potential to create long-term economic advantages for Canada.

The CFREF program is well aligned with government priorities on innovation, talent recruitment, and equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI). The evaluation found that grantees have made some progress in implementing their EDI plans, which is a requirement of the program, to ensure that individuals from the four designated groups (women, visible minorities, Indigenous Peoples and persons with disabilities) have an equal opportunity to participate in and benefit from the program. However, despite efforts to date, program self-identification data indicate that there is an overall underrepresentation of individuals from the four designated groups within the program, particularly among Indigenous Peoples (currently 0.5% of participants) and persons with disabilities (currently 2% of participants). Grantees are aware that this is an important priority for both the agencies and the federal government, and many acknowledge that there is still work to be done to improve diversity in their CFREF teams and governance structures.

Given that support for early career researchers (ECRs) was first introduced as a priority by the Government of Canada in 2018, three years after the CFREF program was launched, this priority did not influence the program’s design at that time. Currently, TIPS collects information on the number of ECRs involved in the initiatives at mid-term, which suggests that the program’s contribution to this priority is of interest to management. However, CFREF’s objectives and expectations of grantees as it relates to supporting ECRs have not been clearly defined in the program information.

The implementation of CFREF

The evaluation has not identified gaps or shortcomings that would raise reasonable concerns about the grantees’ governance structures or their capacity to adequately manage their grants. The flexibility that CFREF offers grantees to build their own governance structure was identified as a key strength of the program by many key informants. The strategic focus appears to evolve over time and the range of funding allocation mechanisms used by grantees is fairly traditional (e.g., competitive processes), but the unifying framework of a common research program distinguishes CFREF grants from other funding the institutions and researchers receive. Grantees have, however, experienced some challenges and delays in the start-up phase, which are common for large-scale funding programs, and have led to a need for some grantees to seek and receive no-cost grant term extensions of two years. At roughly mid-way through their funding, grantees had spent 23% of the $1.2 billion awarded for their grants. As such, the use of funds over time should be carefully monitored going forward, particularly in light of the fact that the current COVID-19 pandemic may cause additional delays.

Participants, partnerships, collaborations and infrastructure

At the time of the evaluation, CFREF-funded activities had engaged more than 6,700 individuals occupying various research or support functions, predominately graduate students (36%), faculty members (23%) and postdoctoral fellows (13%). CFREF participants identified several benefits to participating in the grant, including access to an enhanced interdisciplinary research and training environment, state-of-the-art research facilities and equipment, and complementary training programs that develop HQPs’ non-academic skills (e.g., knowledge translation and commercialization) and employability.

Grantees have engaged more than 600 partners and close to 1,500 collaborators, at the national and international levels. The exact contribution of CFREF in allowing these partnerships and collaborations to emerge or expand cannot be measured precisely, but evaluation findings indicate that receiving grants of the magnitude of CFREF has facilitated this outcome. As of the end of the 2018-19 fiscal year, one-half of the $1.3 billion committed by the funded institutions and their partners for the seven-year period covered by the grants had been secured. In addition, these partnerships and collaborations have provided grantees with growing visibility and recognition at national and international levels, as well as access to a wider range of infrastructures, equipment and expertise, both from a scientific and commercialization perspective.

Over the seven-year grant term, the 17 grantees have projected to spend a combined total of $255 million on research facilities, equipment and supplies. The CFI has played a critical role in providing complementary support to ensure that the required infrastructures are available to conduct the funded research. Data from Competition 1 grantees show that these five institutions had secured $71 million since drafting the CFREF proposals up until mid-term.

Program design and delivery

The processes relating to the first two competitions were fairly challenging for all involved. Given the large scale of the funding provided by CFREF and the significant latitude for applicants in terms of determining their scientific and institutional strategies, there were many uncertainties surrounding the application process, and both successful and unsuccessful applicants had to seek more guidance and clarification from TIPS than they had received. As for the ongoing implementation of the grants, grantees would generally appreciate having more sustained communications and interactions with TIPS to ensure that they are proceeding in accordance with the expectations of the funding agencies.

The evaluation also identified the strengths and limitations of the current monitoring and reporting activities undertaken by TIPS and CFREF grantees. The performance information collected by TIPS through the annual and the mid-term reports was valuable for this evaluation and provided a good overall understanding of the grantees’ activities and the progress made by the program toward its immediate outcomes. Nonetheless, some important areas for improvement were identified, including: reviewing the reporting templates in order to ensure greater consistency and enhance quality of data collected though these reports, clarifying the purpose and intended use of performance data collected through the PMPs, encouraging grantees to clearly articulate a long-term vision for what they want to accomplish through their grant, and that TIPS explore the possibility of instituting an end-of-grant report. This would allow grantees to document their overall experience with their CFREF grant, the results achieved, the expected legacy or long-term impacts of the grant, key challenges and lessons learned. This reporting would also facilitate TIPS’ efforts to document and report on program outcomes and would provide evidence for future evaluations.

Recommendations

Although it was too early in the program’s lifecycle to assess the longer-term expected results of investing at the institutional level, the program remains relevant, has largely met its immediate outcomes (i.e., governance structures and funding allocation processes within institutions, partnerships, collaboration, attraction/retention of teams) and demonstrated progress toward some of its intermediate outcomes (i.e., infrastructures, training environments). This conclusion is supported both by the data collected for this evaluation and the results from the mid-term review of the first five grants. It should be noted, however, that there remain some questions regarding how the transformational changes brought about by the CFREFs will be sustained. The manner in which grantees described their plans for sustaining the transformative changes largely focused on what other funding would be sought to allow them to maintain the momentum of their research activities once their CFREF grants ended. Although grantees described some activities and early outcomes that are indicative of legacy and point to long-term institutional impacts of the program (e.g., new faculty positions created in areas of the CFREF and enhancements to the training environments), the overall results from the mid-term review and the evaluation suggest that securing funding for sustaining the transformational changes brought by the CFREFs could be a challenge following the end of the granting period.

An analysis of cost-efficiency data suggests that the CFREF program has been delivered by TIPS in a very cost-efficient manner to date, however, evaluation findings suggest that TIPS’ administrative costs of delivering the program may be too low for supporting effective implementation and monitoring. Specifically, grantees and applicants identified some challenges with respect to design and delivery of the CFREF program, some of which could be mitigated by improving communications between TIPS and grantees/applicants. The evaluation also identified strengths and limitations of the current monitoring, reporting and performance measurement activities. Based on these conclusions, the evaluation offers the following recommendations to improve the CFREF program.

Recommendation 1: Improve alignment of the CFREF program with government priorities on equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI), and support for early career researchers (ECRs), by:

- Continuing to ensure that grantees have implemented plans related to the representation of individuals from the four designated groups and monitoring the participation of these groups. If the distribution of CFREF participants does not improve on pace with program expectation, consider implementing more specific guidance or EDI targets in future competitions; and

- Clarifying the CFREF program’s role and expectations of grantees in supporting ECRs, given that it is a current priority for the government.

Recommendation 2: Continue to track the rate at which grants are being expended and consider no-cost extensions as required, especially as the COVID-19 pandemic may cause additional delays.

Recommendation 3: Strengthen monitoring and reporting activities undertaken by grantees, in order to improve the ability to understand and assess longer-term impacts, by:

- Reviewing the annual progress and mid-term report templates to ensure that key definitions are clarified, and that the same format is used for common data elements across these reporting tools in order to enhance consistency in reporting and comparability of data;

- Improving the utility of the PMP for both TIPS and grantees by requiring applicants to clearly articulate what the grant is expected to achieve in the short and long term and how (i.e., its post-grant legacy), and identify relevant grant-specific performance indicators based on the grant’s transformational logic, in addition to common CFREF program-level indicators; and

- Instituting an end-of-grant report, based on the current model for the mid-term report, in order to better understand and document outcomes and results achieved over the life of each grant.

Recommendation 4: Further enhance communications and support to applicants and grantees by:

- Ensuring that comprehensive guidance is provided by TIPS to funding applicants should there be a new competition; and

- Maintaining sustained communication with grantees during the implementation phase of their grant.

1.0 Introduction

This document constitutes the final report of the evaluation of the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (CFREF). SSHRC evaluators and an evaluation consulting firm (PRA Inc.) collaborated to design and implement this evaluation. As the program was launched in 2014, this constitutes the first evaluation of CFREF and covers its initial four fiscal years of operations, from 2015-16 to 2018-19. The evaluation was conducted in accordance with the federal government’s Policy on Results (2016) and section 42.1(1) of the Financial Administration Act, which requires each ongoing federal program of grants and contributions to be evaluated every five years with respect to its relevance and effectiveness.

The following subsections included in this introduction provide a brief overview of CFREF, of the purpose and scope of the evaluation, and a summary of the methodology used to evaluate CFREF. A more detailed description of the methodology is included in Appendix B.

1.1 Overview of CFREF

As part of its Economic Action Plan, the federal government announced the establishment of CFREF in its February 2014 budget. At that time, it set aside $1.5 billion over 10 years to support this new program, which was expected to strengthen the capacity of world-class postsecondary institutions in Canada to recruit leading researchers, secure promising partnerships, and advance breakthrough discoveries. The federal government’s ultimate goal was to “help Canadian post-secondary institutions excel globally in research areas that create long-term economic advantages for Canada” (Government of Canada, 2014b, p. 115).

At the time of the evaluation, CFREF had funded 18 seven-year grants through a competitive peer-review process to 17 postsecondary institutions (i.e., 17 grantees). These grants support the implementation of institutional and scientific strategies in research areas where these institutions have already demonstrated strength and leadership. Described succinctly, the “institutional strategy” refers to the overall vision and approach that the institution as a whole is proposing to integrate the CFREF grant into its existing governance and operations, while the “scientific strategy” refers to the actual research program that the institution is proposing to undertake, including the engagement of partners and collaborators and the research program’s anticipated impact.

Institutions that are awarded CFREF grants may use the funding to cover both direct and indirect costs of researchFootnote 1:

- Direct costs may include, among other things, expenses related to compensation (salaries, scholarships or stipends) for students, postdoctoral fellows, new faculty members, technicians and other research professionals, as applicable. They may also include expenses related to some equipment (typically valued at less than $300,000) and supplies, and the dissemination of research activities. Finally, direct costs may include seed funding to conduct peer-reviewed competitions that are aligned with the scientific strategy of the institution.

- Indirect costs may include, among other things, expenses related to the renovation and maintenance of research facilities, research resources (e.g., library holdings), intellectual property and licensing, and the management and administration of the grant. Indirect costs cannot exceed 25% of the total grant amount.

The Tri-agency Institutional Programs Secretariat (TIPS) is responsible for the administration of the program, including managing the peer-review process of proposals by panel members and the release of funds to CFREF grantees, ensuring ongoing eligibility of institutions to receive funding, as well as ongoing monitoring and management of funding agreements signed with each institutional grantee. Thus far, TIPS has managed two competitions for CFREF grants, worth $1.25 billion:

- The results of Competition 1 were announced in July 2015, when $350 million was awarded across five grants. The value of each grant ranges between $33.5 million and $114 million.

- The results of Competition 2 were announced in September 2016, when $900 million was awarded across 13 grants. The value of each grant ranges between $33.3 million and $93.7 million.

For each of the two competitions, funding applications were expected to address the research priority areas outlined in the 2014 Science, Technology, and Innovation Strategy, namely: environment and agriculture; health and life sciences; natural resources and energy; information and communication technologies; and advanced manufacturing (Government of Canada, 2014a, p. 20). In 2019, TIPS announced that the third competition for CFREF funding is expected to be launched in 2021-22 (Government of Canada, 2014c).

1.2 Evaluation purpose and scope

The primary purpose of the evaluation was to provide senior management from the tri-agencies―the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC)―with an assessment of the relevance and immediate outcomes of CFREF as per the program’s logic model (included in Appendix A). As it was conducted four years into the delivery of the CFREF program, it was too early to assess the longer-term expected results of investing at the institutional level, or to conclude if the program’s focus on funding at the institutional level confers specific advantages or disadvantages compared to funding at the researcher or project level. Aspects of design and delivery were looked at to help support the ongoing management of the program. More precisely, the evaluation addressed the following five questions:

- To what extent does CFREF continue to address a unique need and align with government priorities?

- How, and to what extent, have institutions implemented structures and processes for prioritizing funding toward research in CFREF priority research areas?

- To what extent has high-caliber, diverse and interdisciplinary research talent been attracted, retained and trained?

- To what extent have funded institutions created or strengthened partnerships, collaborations and infrastructure to enhance research capacity?

- To what extent is the design and delivery of CFREF effective and efficient?

In accordance with the Directive on Results, the evaluation also took into account government-wide policy considerations such as equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI). The evaluation has documented the experience of grantees in integrating EDI considerations in the implementation of their activities, particularly as it relates to recruiting new participants and establishing collaborations.

At the time of data collection for this evaluation, Competition 1 grantees had completed approximately four years of activities, while Competition 2 grantees had completed approximately three years of their seven-year grant term. Although it is too early in the life of these grants to assess intermediate and long-term outcomes, all 18 grants were included in this evaluation in order to build our understanding of how CFREF grants have been administered to date, what progress has been made towards short-term goals and objectives, and how the CFREF program as a whole is unfolding and being received within institutions.

Finally, it should be noted that one of the key components of the monitoring activities related to CFREF is a mid-term review of each individual grant, which is expected to occur by the end of the fourth year of the grant. This process, managed by TIPS, starts with a mid-term report that is prepared by the grantee. This report is then reviewed by external experts who provide written assessments. On that basis, a multidisciplinary review panel that includes individuals with expertise on the subject matter of the CFREF grant conducts a site visit and provides its assessment to the Mid-term Board that, in turn, provides recommendations that are subject to approval by the CFREF Steering Committee.Footnote 2 Footnote 3 At the time of this report, the mid-term review for all five Competition 1 grants had been completed. Ultimately, the evaluation and the mid-term reviews played complementary roles, with the former addressing the relevance and performance of the CFREF program as a whole, and the latter providing assessments of each grant to date, with latitude to make recommendations for improving scientific and implementation strategies.

1.3 Evaluation methodology and limitations

The evaluation involved multiple lines of evidence, including a review of program documents and some relevant literature, a review of CFREF administrative data (comprising annual progress and financial reports from all grantees, as well as the final results of the mid-term peer review for the first five grantsFootnote 4), case studies of the five Competition 1 granteesFootnote 5, interviews with key informants (n=62 interviews involving 92 individuals)Footnote 6 and a web-based survey of CFREF core team members from all 18 grants.Footnote 7 The overall response rate for the survey was 20% (n=1,144/5,671), but varied by institution (between 6% and 33%) and it was slightly higher among faculty (27%, n=410/1,505). A detailed description of the methodology is included in Appendix B.

The methodology for this evaluation presented some limitations described in this subsection, but these limitations did not prevent all evaluation questions from being adequately addressed. First, although unsuccessful institutional applicants to the CFREF program were interviewed as part of this evaluation, researchers at recipient institutions who were unsuccessful in receiving CFREF funding, and researchers who work in similar research areas (as those of the CFREF grants) at universities that did not receive a CFREF grant, were not interviewed as part of this evaluation. This reflects the fact that the evaluation focussed on CFREF as a whole and was not meant to evaluate each grant individually. As such, the primary goal was to obtain the views of researchers funded through CFREF, and also receive some insights from applicants to the CFREF program who were not successful.

Second, some of the administrative data reviewed as part of this evaluation was not reported consistently across CFREF grantees (e.g., timeframe of reported data). In addition, at the time of the evaluation, the mid-term reports were still not submitted by Competition 2 grantees. As such, more detailed administrative data was available for Competition 1 grantees. In order to address these issues, administrative data was aggregated across all grantees only when it was feasible to do so.

Third, the response rate of the survey of CFREF participants varied among CFREF grants (between 13% and 33% except for one grant where the response rate was 6%). Despite these variations, a sufficient number of respondents from both faculty and HQP was obtained to allow for the survey results to be considered representatives of all 18 grants. Moreover, the sample of survey recipients (i.e., lists of CFREF participants) was validated to ensure that the responses of CFREF participants with only peripheral involvement in the grant were excluded from the dataset.

2.0 The relevance of CFREF

Evaluation Question 1: To what extent does CFREF continue to address a unique need and align with government priorities?

CFREF is the only large-scale funding program that is specifically designed to support the implementation of scientific strategies at an institutional level and to allow grantees to strengthen their institutional position in a specific field of research. It builds on and complements other government initiatives and provides the government with a unique vehicle for investing in targeted priority research which have the potential to create long-term economic advantages for Canada. Other large-scale funding opportunities in Canada, including the Innovation Superclusters Initiative and New Frontiers in Research Fund (NFRF), may be particularly synergistic with CFREF. The Transformation stream of NFRF, for instance, funds large-scale, world-leading, Canadian-led interdisciplinary research projects, while the Superclusters initiative supports innovative economic growth in Canada. Through case studies and key informant interviews, some grantees identified NFRF as a potential source of funding which might allow them to extend their research activities and maintain momentum once their CFREF grants end. Potential synergies might also emerge with superclusters, as some CFREFs are engaged in research areas that are similar to some of the areas targeted by superclusters. Given the young age of these programs, however, there have been no formal collaborations between CFREF grants and superclusters to date, and the extent of potential synergies is not yet known.

The CFREF program is well aligned with the government’s priorities on innovation, talent recruitment, partnerships and equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI). Since CFREF was launched before the introduction of support for early career researchers (ECRs) as a government priority in Budget 2018, the program literature is currently silent on the nature and extent of CFREF’s role in supporting ECRs. Given the current focus on this priority, there remains an opportunity to define and articulate the role of CFREF with respect to supporting ECRs.

This section provides a brief assessment of how the relevance of CFREF has evolved since the program was launched in 2014. This includes looking at CFREF’s niche in the current ecosystem of federal research funding and how CFREF has been positioned in relation to government priorities. The brief exploration of these issues was based on a literature review complemented with perceptions of interviewees.

2.1 CFREF’s niche in the current ecosystem of federal research funding

Any component of an ecosystem of research funding is bound to co-exist and interact with other programs that may support, differently prioritize, duplicate or complement what it is attempting to achieve. As such, the predominance of the concept of an ecosystem when assessing research funding reflects the inescapable fact that any level of excellence in research is never the result of a single initiative. It is rather the achievement of the ecosystem as a whole. In this context, the primary goal when assessing any research funding program, including CFREF, is to better understand its relative niche and contribution, if any, toward this goal of research excellence.

The rationale for introducing CFREF

Research as engine of growth

As noted in the introduction, the federal government initially included CFREF as part of its Economic Action Plan in 2014, and the rationale for the investment relied heavily on the program’s anticipated ability to create long-term economic advantages for Canada. The fact that the funding was directed toward five priority research areas with high levels of commercialization potential, and would involve an array of partners, both public and private, further illustrates this vision.

It has, in fact, long been recognized that research and development (R&D) and the innovation it facilitates are an essential requisite for sustained economic growth (Canada’s Fundamental Science Review Panel, 2017, p. 21; Research, Technology & Development Topical Interest Group, 2015, p. 13). Despite its relatively small population base, Canada has historically positioned itself favourably when it comes to knowledge creation. As of 2014, Canada was among the top 10 producers of scientific publications, alongside countries with far larger populations and R&D investments such as the United States, China, Germany, the United Kingdom and France (Council of Canadian Academies, 2018, p. 37).Footnote 8

Yet, at the time that CFREF was launched, Canada was starting to lag at the international level in relation to its capacity to remain competitive in research and development (R&D) investments, knowledge creation, and its capacity to attract and retain world-leading researchers (Canada’s Fundamental Science Review Panel, 2017; Council of Canadian Academies, 2018; OECD, 2018; Scherer, 2014). As it announced the creation of CFREF, the federal government emphasized that the level of international competition for the best minds, partnership opportunities and breakthrough discoveries implied was such that Canada could not afford to be complacent and had to support its world-class institutions to advance their greatest strengths and maintain their competitiveness on the global stage (Government of Canada, 2014b, p. 115).

Investing at the institutional level

Arguably, one of the most distinguishing features of CFREF is its focus on supporting large-scale strategic research initiatives led by institutions, rather than supporting individual researchers or research projects. CFREF further narrows its scope by targeting postsecondary institutions that have already distinguished themselves as leaders in specific fields of research. As such, the purpose of CFREF is not to enable institutions to build foundational capacity in a field of research. Instead, the aim of the program is to further support well-established institutions in a specific field to significantly expand their pre-strong pre-existing capacity to undertake research, attract top minds, and build partnerships. Some stakeholders, echoing an issue raised by the Fundamental Science ReviewFootnote 9, questioned whether the federal government’s decision to concentrate resources on a small number of grants represents the best funding model, compared to allocating smaller amounts of money to a larger pool of researchers and/or institutions, and expressed concern that this approach may lead to an overconcentration of resources in a subset of institutions. This view was expressed particularly by those applicants who had not been successful in securing CFREF funding. Other interviewees, however, (both funded and unfunded) lauded this approach, saying that it shows strong commitment by the federal government to invest in priority areas and raise the international profile of Canadian postsecondary institutions.

As for the types of institutions that may access CFREF support, administrative data to date demonstrates that participating institutions and grantees vary in size and regional distribution. As documented in Table 1, the list of existing CFREF recipients range from Laurentian University (9,500 students enrolled in 2019) to the University of Toronto (just over 91,000 students enrolled in 2019). In fact, CFREF primarily targets a locus of excellence within an institution, rather than the institution itself.

| Institution sizeFootnote 10 | Competition 1 | Competition 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applicants | Recipients | Success rate* | Applicants | Recipients | Success rate* | |

| Small | 4 | 0 | 0% | 4 | 1 | 25% |

| Medium | 12 | 2 | 17% | 11 | 4 | 36% |

| Large | 15 | 3 | 20% | 14 | 8 | 57% |

| Other | 5 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 36 | 5 | 14% | 29 | 13 | 45% |

*Success rates represent the proportion of complete grant proposals that were successful.

Source: CFREF application data. Classification of institutions’ size is based on the Canada Research Chairs (2017).

In sum, by its very nature, CFREF builds on other programs that allow for research inquiries to be pursued and for leadership in targeted research areas to emerge in the first place. For instance, eight Canada Excellence Research Chairs (CERC)Footnote 11 and Canada C150 Research Chairs award holders (current and emeritus) and up to 83 Canada Research Chairs (CRC) award holders have been involved in CFREF grants awarded in the first competition. During interviews conducted as part of the evaluation, representatives from funded institutions also emphasized the contribution of CFI grants in building the research environment that positioned the institution to successfully compete for a CFREF grant. Put simply, in cases where a broad eco-system of research funding and infrastructure have already enabled institutions to establish programs of research excellence, CFREF provides a springboard for institutions to further expand their institutional vision and leadership role.

CFREF’s niche in relation to NFRF and the Superclusters

When assessing the niche of CFREF in the overall ecosystem of research funding in Canada, two other programs, the New Frontiers in Research Fund (NFRF) and Innovation Superclusters Initiative, were flagged by stakeholders as being of particular interest in terms of whether there would be connections or synergies with CFREF.

New Frontiers in Research Fund

When planning was initiated for this evaluation, NFRF was a very new program. It was launched in 2018-19, with an initial investment of $275 million over five years, and $65 million annually thereafter (Government of Canada, 2020d). NFRF provides funding through three streams to support ground-breaking research in Canada. Of these, NFRF’s Transformation stream is perhaps the most comparable to CFREF as it aims “to support large-scale, Canadian-led interdisciplinary research projects that address a major challenge with the potential to realize real and lasting change” (Government of Canada, 2020c).

While the Transformation stream of NFRF and CFREF share the broad goal of supporting large-scale, world-leading Canadian research, they also have several distinct characteristics. Most notably, NFRF differs from CFREF as it does not provide an institutional grant, rather supports a team of researchers with one Nominated Principal Investigator, who becomes the award holder. Although CFREF grantees may establish collaborations with international and/or inter-institutional players, the institutional focus of CFREF uniquely positions it as a vehicle for drawing together faculty and HQP from different disciplines within an institution and building internal strengths in support of a common institutional vision. CFREF is also intended to support institutional programs of research in specific priority areas, while NFRF may fund projects outside of these research areas.

Given these key differences, the evaluation determined that CFREF and NFRF fill unique roles in the Canadian funding landscape, however, there may be potential for synergies between the two programs. In particular, the scale of funding that NFRF provides, through its Transformation stream, combined with its objective to support to large-scale, interdisciplinary research projects could potentially support research in some of the areas funded by CFREF. During interviews, some stakeholders spoke about ways in which they might extend their research activities and maintain momentum once their CFREF grants end. Although it is too early at the time of this evaluation to comment on the nature of any subsequent funding or speculate about grantee’s participation in future funding competitions, several grantees expressed a view that NFRF might serve as a potential “next step” to provide some support to sustain their research activities following the end of their CFREF grants. These respondents felt that NFRF might be a particularly good fit for some of the projects currently supported by their CFREF grants especially given the interdisciplinary research teams and multidisciplinary approaches to research that have been developed under CFREF to date.

Superclusters

At the time of the evaluation, there was an interest in better understanding how CFREF and the Innovation Superclusters Initiative would interact. Unveiled as part of the 2017 budget and managed directly by Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED), this initiative operates with a total budget of up to $950 million over five years, starting in 2017-18 (Government of Canada, 2020b). To date, five superclusters have received funding to address challenges concerning digital technology, protein industries, manufacturing, artificial intelligence and oceans. These superclusters are led by industry consortia, and the private sector is expected to match dollar for dollar the federal investment. Each supercluster involves a large number of industrial partners, as well as some public and academic entities.

The primary purpose of superclusters is to “energize the economy and become engines of growth” (Government of Canada, 2018e). As such, the initiative shares with CFREF a common goal of sustaining innovative economic growth in Canada. Both programs also aim to recruit and retain new talent and promote multisectoral collaborations and partnerships, which help position Canada as a world-leading innovation hub. Beyond this, however, the two programs operate in largely different spheres. As noted during interviews, the fact that CFREF is decisively led by academia and the superclusters are just as decisively led by industry shapes their actions and priorities. Whereas CFREF is pursuing innovative research programs with promising scientific, research or social applications, the superclusters are focusing on the later stages of the R&D continuum, with the expectation that short-term commercialization benefits will be realized through new products, new manufacturing processes, new technologies or new commercial strategies.

In the larger picture, the two initiatives play different roles and the extent to which researchers and/or projects under these initiatives will formally or informally interact remains uncertain. It is worth noting that some of the universities involved in CFREF grants do participate in the activities of superclusters, however, there have been no instances yet where a CFREF research grant and a supercluster directly collaborate based on a shared strategy.

2.2 Alignment with current government priorities

The federal context has evolved considerably since CFREF was launched in 2014. In particular, the change in government resulting from the 2015 federal election led to a new approach in setting priorities related to research and innovation.

Priorities as of 2014

As already noted in the description of CFREF, the first two competitions under CFREF required applicants to address at least one of the priority areas included in the 2014 Science, Technology, and Innovation Strategy. The evaluation confirms that all 18 grants are directly reflecting these priorities. As indicated in Figure 1, these grants are almost equally distributed among priority areas, except for advanced manufacturing where only one grant focussed primarily on it (quantum materials). However, these priority areas are not exclusive of each other, and most grants also address other priority areas.

Source: TIPS administrative data

Figure 1 long description

| Priority research area | Number of grants |

|---|---|

| Advanced manufacturing | 1 |

| Information and communications technologies | 4 |

| Natural resources and energy | 4 |

| Health and life sciences | 4 |

| Environment and agriculture | 5 |

Source: TIPS administrative data

Priorities as of 2020

Since the 2015 election, the government has repeatedly emphasized the importance of fostering innovation, supporting scientific research and attracting new research talent (Government of Canada, 2016a, p. 110, 2017a, p. 17, 2018a, p. 85, 2019, p. 121). This has included, among other things, new investments in scientific research, including the NFRF, and the launch of the Innovation and Skills Plan, which contains many components, such as the Innovation Superclusters Initiative and the Strategic Innovation Fund (Government of Canada, 2020a)(Government of Canada, 2019). In addition, the government has pursued horizontal priorities, particularly as they relate to EDI and support to ECRs. In announcing, in its 2018 budget, an investment of nearly $4 billion in Canada’s research system, the federal government underscored that this investment “is tied to clear objectives and conditions so that Canada’s next generation of researchers―including student, trainees and early career researchersis larger, more diverse and better supported” (Government of Canada, 2018a, p. 82).

The priority areas included in the 2014 Science, Technology, and Innovation Strategy, while still relevant, are no longer acting as the primary driver to inform funding programs across government. There is scope within the program framework which allows for government to review these areas before new competitions. This is reflected in the recent practice of funding agencies to identify priority areas in the context of particular research funding program competitions. For instance, the 2016 CERC competition used the priority areas of the 2014 Science, Technology, and Innovation Strategy, but also added new research areas related to social inclusion and innovative society, and open areas of inquiry to be of benefit to Canada (Government of Canada, 2018d).

In addition to the priority areas that were targeted at the time of the CFREF competitions, the evaluation confirms that the CFREF program continues to support the broader horizontal federal priorities, such as those relating to EDI and ECRs. In terms of EDI, at the outset, applicants to the program had to include an “equity plan outlining how career and training benefits derived from the opportunities associated with the initiative will be made available to individuals from the fours designated groups (women, visible minorities, Indigenous Peoples and persons with disabilities)” (Government of Canada, 2016e). During interviews, representatives from funded institutions were very conscious of the importance placed on EDI and on the expectation that progress in that regard would be achieved and properly documented.

What has not been as clearly defined in the program information are CFREF’s objectives and expectations of grantees as they relate to supporting ECRs. As noted earlier, supporting ECRs was introduced as a government priority in Budget 2018, two years after the last CFREF competition in 2016. CFREF grants are logically intended to enhance the environment in which participating ECRs evolve. However, at a more fundamental level, the evaluation found that the expected impact of CFREF on ECRs remains to be more clearly defined, regardless of whether or not senior management determines that the program has a role to play in implementing this priority. TIPS currently collects information on the number of ECRs involved in the initiatives at mid-term which suggests that the program’s contribution to this priority is of interest to management.

3.0 The implementation of CFREF grants

Evaluation Question 2: How, and to what extent, have institutions implemented structures and processes for prioritizing funding toward research in CFREF priority research areas?

The evaluation has not identified gaps or shortcomings that would raise reasonable concerns about the grantees’ governance structures or capacity of grantees to adequately manage their grants or leverage funding at this point in time. Although governance structures vary between funded institutions, the flexibility that CFREF offers grantees to build their own governance structure was identified as a key strength of the program by many key informants. In particular, having a framework by which to engage senior personnel (i.e., a vice-president of research), to establish a dedicated administration team for the grant and to connect with other grantees were identified as key features that support the strategic direction of the grant. The strategic focus appears to evolve over time and the mid-term review process, involving expert peer review, plays an important role in challenging grantees to demonstrate that the scientific direction of their initiatives is on track to help the institutions become world leaders in their area.

Grantees reported experiencing some challenges and delays in the start-up phase. In particular, many reported that the first year of the grant was largely spent establishing a detailed implementation plan and putting their governance and funding allocation structures into place. Evaluation findings point to the important role that TIPS has in helping institutions understand the granting agencies’ expectations (e.g., whether their proposed governance structures met the expectations of TIPS) and making them aware of some of the options available to them based on lessons learned at other institutions (e.g., examples of successful practices or governance models adopted by other grantees). The delays in the start-up phase, which are common for large-scale funding programs, have led to a need for some funded recipients to seek and receive no-cost grant term extensions of two years. The use of funds over time should be carefully monitored going forward, particularly because the current COVID-19 pandemic may cause additional delays.

The range of funding allocation mechanisms used by grantees remains fairly traditional (e.g., competitive processes), but the unifying framework of a common research program distinguishes CFREF grants from other funding institutions and researchers receive. As of March 2019 (i.e., fourth year for Competition 1 and third year for Competition 2), grantees had spent 22.6% of the $1.2 billion awarded to cover both direct and indirect costs of research related to their grants. At the time of the evaluation, funded institutions and their partners had committed $1.3 billion in additional funding to support the scientific and institutional strategies of the grantees. Partners include the public sector, private businesses and other academic institutions. Another $194 million from other federal programs (other than the CFI) is also supporting these research activities.

While it is still early in the program’s lifecycle, overall results from the mid-term review and interviews with institutions suggest that securing funding for sustaining the transformational changes brought by the CFREFs could be an issue following the end of the granting period. Some grantees feel that NFRF could potentially help to fill the gap for project funding and allow them to maintain momentum with their research activities once their CFREF grants end.

This section of the report turns to the actual implementation of CFREF grants at the institutional level. The evaluation first relied on the mid-term reviews administered by TIPS to determine whether or not the implementation of the grants from the first competition has met expectations. Specifically, the TIPS Steering Committee approved all five grantees from the first cohort for continued funding with recommendations. The interviews, case studies and administrative data review conducted as part of the evaluation complemented this exercise by providing a high-level overview of the collective experience of the 17 grantees to better understand the range of implementation strategies used to date, challenges encountered and lessons learned.

3.1 Grant governance models and funding allocation processes used

Governance structures

The program guidelines provided considerable flexibility for grantees in establishing their governance structure. As part of their proposals, applicants were asked to describe the approach they were planning to use to ensure that the grant would be successfully implemented, including the proposed governance structure and the accountability and decision-making processes (Government of Canada, 2016b).

While no governance structure is identical, and ongoing adjustments are implemented as required, the grantees have typically included at least the following components:

- An overarching committee (e.g., a steering or executive committee) that oversees the institution’s progress in implementing the grant and in ensuring that the vision behind the scientific and institutional strategies being implemented through CFREF is adequately integrated in the institution’s strategic direction. The committee normally includes the vice-president of research (or equivalent), along with other senior administrators (e.g., deans) and faculty members. The grant leads (scientific and/or administrative), as well as other committees, report to this committee;

- Advisory committees, involving both internal and external scientific experts and partners, that provide advice or make recommendations in all aspect of the grant management, including the allocation of funds, as applicable;

- A peer-review committee that involves external experts, supporting the selection of specific projects to be funded through the grant; and

- An executive director position (or equivalent) who manages activities and processes on an ongoing basis. Additional team members are normally assigned to support the executive director, including, for instance, communication officers and administrative support (who may be assigned on a part-time or full-time basis).

In some cases, the CFREF grant has been integrated into existing institutes such as the Institut Quantique in Sherbrooke, the Stewart Blusson Quantum Matter Institute in Vancouver, the Sentinelle Nord in Laval and the Global Institute for Food Security in Saskatchewan. In other cases, such as Medicine by Design in Toronto, the grant has been set up as a horizontal initiative that is managed with the involvement of applicable faculties/departments. In all cases, however, the grantees have created a distinct brand for their CFREF grant, including a website and other communication means (e.g., presence on social media).

Key features that support the strategic direction of the grant

The experience gained by the first 17 CFREF grantees is shedding light on factors that contribute to a governance structure that can effectively support the strategic direction of the grant.

First, the flexibility that CFREF provides to each grantee in determining the most appropriate governance structure was perceived as a key strength of the program by many interviewees. Each postsecondary institution in Canada brings its own history, distinguishing features, organizational culture and governance model. The type of scientific research being undertaken through each grant and their unique strategic direction further adds to the variety of governance approaches that may be required.

Second, having the vice-president of research (or equivalent) directly involved in the management of the grant is perceived as particularly beneficial. As the fundamental goal of CFREF is to allow for the implementation of institutional and scientific strategies that will strengthen the positioning of the institution in a specific field of research, it is desirable to involve individuals who can effectively bridge the CFREF grant and the entire strategic vision of the institution.

Third, the range of activities undertaken, and the various monitoring and reporting requirements associated with the grant, necessitate considerable time and resources. Having an administrative team specifically dedicated to the grant, including a full-time executive director (or equivalent), is emerging as a good practice. As noted during interviews, dedicating personnel, including an administrative lead, to manage the administrative aspects of the grant is critical for ensuring that the scientific lead has sufficient time to dedicate to managing the scientific aspects of the grant.

Finally, the ability of grantees to connect and share lessons learned offers many benefits, and this appears particularly true when it comes to sharing lessons learned on the effective, strategic management of a large institutional grant such as CFREF (e.g., at the annual summit for CFREF grantees or through individual exchanges).

Challenges encountered

Some of the funded recipients identified challenges experienced during the implementation of their grant, particularly as it relates to the early period of implementation. The evaluation primarily drew on the case studies of Competition 1 awardees to identify these challenges, although the experiences of Competition 2 awardees were also considered. The three primary challenges that emerged are:

- The time and resources required to establish the governance structures and the detailed implementation process for the grant: For grantees, a considerable portion of the first year of the grant implementation was devoted to establishing the required governance structure, including the recruitment of the core team tasked with managing the grant. In doing so, grantees often had to modify the governance structure from what they had initially included in their application to address the full range of practical considerations that the implementation of their grant entailed. To various extents, this process deferred the actual implementation of the scientific strategy and required some grantees to allocate more resources than initially anticipated to the administration of their grants. This challenge was more predominant among Competition 1 grantees, which were provided with a particularly short timeframe to develop their proposals.Footnote 13

- Uncertainties related to the range of potential governance models: As part of the application process, CFREF provided applicants with considerable flexibility in determining the governance structure that they would use to manage the overall grant, including the allocation of funding. While grantees highlighted several advantages associated with this flexible approach, some noted that it was sometimes challenging to understand whether the structure they had adopted would meet any set expectations on the part of the program. For instance, during interviews, some grantees indicated that they would have appreciated additional information to clarify the instructions posted on the program’s website but were not able to secure it. Without being more prescriptive, it appears that additional assistance from TIPS in guiding some grantees as they finalize their governance model would be helpful, particularly in light of the size of the grants that CFREF provides.

- Managing researchers’ expectations during the implementation of the scientific strategy: Following the awarding of grants, institutions have had to implement processes that would allow for the allocation of funds to specifically support the goals and objectives of the scientific strategy initially proposed in their application. During interviews, grant administrators have emphasized the importance of clearly communicating this vision to all potential researchers who may wish to undertake research with the support of the CFREF grant. In other words, the very notion that only research activities directly aligned with the scientific strategy would receive funding has, at time, been challenging to communicate to some researchers who wished to pursue their own research agenda. In this context, grant administrators have had to manage expectations, present the various steps initially required to be able to allocate funding, under which conditions, and the timeframe that this would entail. For some grantees, this created some tensions between the grant administrators and the researchers. According to some key informants, this is something that any new grantees should plan for.

Funding allocation processes

CFREF expenditures

In accordance with CFREF administrative guidelines, institutions have been allocating their grant funding to cover both the direct and indirect costs of their scientific and institutional strategies. Notably, indirect expenses were limited to a maximum of 25% of the total CFREF grant. The range of funded activities reflects what would be expected of any research project or program, and typically covers:

- the recruitment of new faculty members and other research professionals;

- scholarships or other forms of support to students and postdoctoral fellows; and

- the provision of support to research activities (seed funding, start-up package, equipment and supplies, travel, etc.).

The 17 grantees’ total projected expenditure over the grant term, as well as the actual expenditures to date (as of 2018-19), is shown in Table 2 below.

| Total expenditure of CFREF funds projected over grant term as of 2018-19* | Cumulative actual expenditure of CFREF funds as of 2018-19 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | % of total | Amount | % of total | |

| Direct Costs | ||||

| Compensation-related expenses | $706,897,441 | 56.5% | $154,071,030 | 54.4% |

| Recruitment and relocation costs | $5,285,190 | 0.4% | $1,888,029 | 0.7% |

| Travel and subsistence | $57,398,370 | 4.6% | $8,650,947 | 3.1% |

| Sabbatical and research leaves | $7,812,839 | 0.6% | $0 | 0.0% |

| Equipment and supplies | $142,107,675 | 11.4% | $41,334,509 | 14.6% |

| Computers and electronic communications | $20,091,874 | 1.6% | $3,913,974 | 1.4% |

| Dissemination of research results and networking | $26,322,901 | 2.1% | $4,410,759 | 1.6% |

| Services and miscellaneous expenses | $65,241,359 | 5.2% | $11,783,437 | 4.2% |

| Direct costs subtotal | $1,031,157,649 | 82.4% | $226,052,685 | 79.8% |

| Indirect Costs (maximum 25% of total grant) | ||||

| Research facilities | $92,648,053 | 7.4% | $28,566,007 | 10.1% |

| Research resources | $18,693,283 | 1.5% | $3,735,813 | 1.3% |

| Management and administration (CFREF) | $85,586,718 | 6.8% | $21,513,328 | 7.6% |

| Regulatory requirements and accreditation | $6,314,590 | 0.5% | $1,085,890 | 0.4% |

| Intellectual property and knowledge mobilization | $14,892,711 | 1.2% | $2,155,548 | 0.8% |

| Indirect costs subtotal | $218,135,355 | 17.4% | $57,056,586 | 20.2% |

| Total | $1,249,293,003 | 100.0% | $283,109,270 | 100.0% |

* Amounts in this column represent the sum of actual spending as of 2018-19 and the projected spending for the remaining of the seven years of the grant term.

Source: 2018-19 annual financial reports

The various activities that are funded by the CFREF grant may also be partially financed by other sources. This is particularly true when it comes to salaries and other related expenses for new faculty members or research professionals and indirect costs. Considering more specifically the experience of Competition 1 grantees in allocating funding for compensation, as shown in Table 3, only 3% of compensation-related expenses used as of 2018-19 were for new faculty appointments, which indicates that CFREFs have been successful in financing new faculty appointments from sources other than the CFREF grant.

Table 3 shows that a total of $13,040,187 has been spent by Competition 1 grantees on compensation-related expenses for research administrative support as of 2018-19. This represents 23% of the total amount spent on compensation-related expenses by Competition 1 grantees as of 2018-19, and 11% of the total grant amount spent by Competition 1 grantees as of 2018-19 (as outlined later in the report, in section 6.1).

| Total of projected cumulative over grant term | CFREF funds used as of 2018-19 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | % | Amount | % | |

| Faculty (new CFREF appointments) | $5,372,273 | 3% | $1,420,326 | 2% |

| Postdoctoral fellows | $31,427,278 | 18% | $10,878,562 | 19% |

| Doctoral students | $21,251,036 | 12% | $6,316,717 | 11% |

| Master’s students | $15,864,571 | 9% | $5,509,351 | 10% |

| Bachelor’s students | $5,637,927 | 3% | $1,835,600 | 3% |

| Research associates | $24,706,503 | 14% | $7,988,706 | 14% |

| Research technical support | $20,229,663 | 12% | $7,264,961 | 13% |

| Research administration support | $43,705,021 | 25% | $13,040,187 | 23% |

| Professional and technical services | $2,537,146 | 1% | $902,852 | 2% |

| Other miscellaneous compensation expenses, including honoraria | $5,106,617 | 3% | $1,982,279 | 3% |

| Total | $175,838,036 | 100% | $57,139,540 | 100% |

Source: 2018-19 mid-term reports

To ensure that the salary of new faculty is paid from a sustainable source, CFREF grants cannot be used to pay for the salaries of faculty who also receive other tri-agency funding. Instead, funded institutions have opted for alternative strategies to support faculty. Some grantees have used CFREF funds to bridge individuals (e.g., covering the first year of salary only) or to cover a portion of the costs, while other institutions have opted for not using CFREF funds to cover salaries, rather using it to provide other support such as start-up packages, access to research personnel or research funds. (Note that grantees’ experiences with the salary restriction are further discussed in section 4). These findings were also confirmed by faculty responding to the survey. As illustrated in Figure 2, over 70% of faculty who had been involved in CFREF indicated that they had received support for their research activities and to hire students and/or staff. No more than 22% of the respondents indicated that their salary as a faculty member had been paid, in part at least, through the CFREF grant. Other forms of support included funding to attend conferences, workshops and other professional activities, as well as assistance with research facilities.

Survey question: To date, have you received funds from the CFREF to support …. (n=487)

Source: Survey of CFREF grant team members

Figure 2 long description

| Use of CFREF funds | Percentage (n=487) |

|---|---|

| Other forms of support | 7% |

| Your salary | 22% |

| Hiring students or staff to work on research projects | 72% |

| Your research activities | 73% |

Source: Survey of CFREF grant team members

As shown in Table 2, 20.2% of CFREF funds that have been spent across the 18 grants as of the 2018-2019 were for indirect costs. This percentage is slightly higher than what grantees initially expected to spend on indirect costs over the duration of the grant term (17.4%). The amounts spent may not reflect the actual total of indirect cost associated with delivering these grants, given that grantees could use resources leveraged from the institutions to support implementation.

As CFREF grants are large and administratively complex to implement, institutions awarded as part of Competition 1 had spent a third of their grants at mid-term on average (33%), which is lower than what they had originally projected immediately following the award of the grant (i.e., 50%). The challenges grantees had experienced in quickly ramping-up the grant were also evident among Competition 2 grantees. Their spending followed a similar pattern, with 19% spent in 2018-19 despite the originally projected 38% by that time. This provides some context for why some grantees have requested and received approval for no-cost grant term extensions of two years as part of the mid-term review to be able to use all grant funds they have been allocated. The use of funds over time should be carefully monitored going forward, particularly given that the current COVID-19 pandemic may cause additional delays.

Allocation processes

Funded institutions have been using a mix of existing and new processes to allocate the funding in accordance with their scientific and institutional strategies. With respect to the allocation of funding for recruitment of researchers and HQP, some institutions have relied on existing policies and processes to guide their funding allocation. In other cases, such as seed funding and other forms of support to research projects, institutions have developed new processes and established new committees to ensure the involvement of the required subject area expertise. This was particularly the case for competitive processes involving peer-review committees.

Researchers who received financial support had most commonly accessed financial support for their research activities through a competitive process (68%) as opposed to an allocation process (24%) (n=357). It was relatively rare to have accessed funding in both ways at the time the survey was administered (3%). Directly allocating funds to researchers generally occurred as part of the start-up phases of the grants to quickly distribute initial research funding, or as part of grantees offering start-up packages to new hires.

CFREF grantees are expected to uphold the principles of fairness, rigour and transparency in allocating funding. However, these processes tend to be complex and involve a degree of discretion and latitude. As part of the survey, 74% of faculty who had been successful in receiving funding through a competitive process indicated that they had no concerns with the process their institution had used (see Figure 3). Given that this group of respondents were successful, it would have been reasonable to expect this percentage to be higher. The most common concerns were lack of transparency, unclear evaluation criteria and perceived conflict of interest in decision-making in terms of funding allocation. In a couple of instances, CFREF leads acknowledged that there were times when communication could have been improved or changes to a process had caused some confusion. Part of this was due to the learning curve associated with getting the process set up.

Source: Survey of CFREF grant team members

Figure 3 long description

| Concerns regarding the competitive process used to allocate research funds | Percentage (n=239) |

|---|---|

| Yes | 20% |

| No | 74% |

| Don't know / prefer not to answer | 6% |

Source: Survey of CFREF grant team members

Even though some concerns were identified, during both the survey and the interviews, the evaluation found that the overall strategies in place to allocate funding reflect the current parameters established in CFREF guidelines. The funding mechanisms also appear to be broadly aligned with the scientific and institutional strategies even though some grantees were currently in the process to narrow their focus further in terms of the number of projects funded or priority subsubject areas (as discussed earlier).

3.2 Leveraging of additional funding

Contributions from funded institutions and their partners

In their grant proposals, applicants were asked to demonstrate the willingness of the lead institution to commit internal resources to support the proposed CFREF initiative, as well as the ability of the institution to leverage additional resources and promote knowledge mobilization through partnerships.

Although CFREF does not have specific requirements to leverage matching funds, the ability of funded institutions to secure funding from partnersFootnote 14 to support their scientific and institutional strategies is one of the the subcriteria considered during the selection process (Government of Canada, 2016b, p. 8). Applicants are asked to provide details on past success in leveraging funds for the institution as a whole and in the specific research area(s) targeted by the CFREF, in addition to details on prospective leveraging plans by identifying key partners who have expressed an interest in collaborating, as well as federal (e.g., tri-agency and CFI) and non-federal funding sources and programs that will be accessed for operating funds to build and strengthen the initiative.

Grantees have successfully leveraged a significant level of funding in support of their strategies. At the end of 2018-19, $1.3 billion had been committed by the funded institutions and their partners for the seven-year period covered by the grants. Considering that the program awarded a total of $1.25 billion in grants, this means that the CFREF funding could end-up being matched or surpassed by the leveraged funding. Nonetheless, it is important to note that in some cases these reported leveraged funds are not exclusively used by researchers involved in the CFREF grants. That is, the reported amounts of leveraged contributions include funds contributed to other beneficiaries who are not involved in the CFREF grants. To be more specific―and as illustrated in Figure 4―by the end of the fiscal year 2018-19, a total of $367.4 million has been committed by Competition 1 lead institutions and their partners. For Competition 2, $965.3 million had been committed from the same sources. This support includes predominantly cash contributions, supplemented by in-kind contributions. In total, 85% of the contributions committed by funded institutions and 72% of the contributions committed by partners are in cash.

Source: 2018-19 annual financial reports submitted by funded institutions

Figure 4 long description

| CFREF grants | Funded institutions | Partners | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competition 1 | $349.3 | $175.6 | $191.8 |

| Competition 2 | $900.0 | $299.2 | $666.1 |

Source: 2018-19 annual financial reports submitted by funded institutions

Looking more closely at the contributions from partners (competitions 1 and 2 combined), 43% of these contributions came from the public sector, while 26% came from the private sector and 21% came from academic institutions (excluding the funded institution). Of note, 20% of contributions from partners came from entities located outside of Canada (see Table 4).

| Types of partners | In Canada | From abroad | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public sector | $321,894,699 | $46,995,220 | $368,889,919 |

| Private sector | $169,649,000 | $56,912,730 | $226,561,730 |

| Academic institutions* | $130,482,104 | $53,422,581 | $183,904,685 |

| Other sectors | $67,907,693 | $10,703,369 | $78,611,062 |

| Total | $689,933,496 | $168,033,900 | $857,967,396 |

*Excluding contributions made by the host institutions.

Source: 2018-19 annual financial reports submitted by funded institutions

At the time of this report, not all contributions committed by the funding institutions and their partners had been secured. As expected, with one additional year of implementation done, grantees from Competition 1 had secured a greater portion of their committed contributions. As illustrated in Figure 5, 62% of the contributions from the funded institutions and 67% of the contributions from the partners had been secured as of the end of 2018-19 fiscal year.

Source: 2018-19 annual financial reports submitted by funded institutions

Figure 5 long description

| Amount secured | Amount committed, but not secured | |

|---|---|---|

| Funded institutions | $108.0 | $67.6 |

| Partners | $128.2 | $63.6 |

Source: 2018-19 annual financial reports submitted by funded institutions

As for Competition 2, 31% of the contributions from the funded institutions and 49% of the contributions from partners had been secured as the end of 2018-19 fiscal year.

Source: 2018-19 annual financial reports submitted by funded institutions

Figure 6 long description

| Amount secured | Amount committed, but not secured | |

|---|---|---|

| Funded institutions | $91.2 | $208.0 |

| Partners | $324.3 | $341.8 |

Source: 2018-19 annual financial reports submitted by funded institutions

Additional funding from the granting agencies and other federal departmentsFootnote 15

As part of the mid-term review process, Competition 1 institutions reported on the funding they have received from the granting agencies (other than through CFREF), which has contributed to advancing their respective scientific strategies. A total of $194 million has been awarded by these agencies since drafting the CFREF proposalsFootnote 16. As illustrated in Figure 7, close to half of this funding has come from CIHR, while NSERC has been the other main contributor. This suggests that there are synergies between CFREFs and other agency and tri-agency funding programs (this conclusion was discussed in section 2.0 of this report).

Source: Mid-term reports submitted by Competition 1 grantees

Figure 7 long description

| Council | Grant by funding council |

|---|---|

| SSHRC | $2.2 |

| Tri-council | $6.0 |

| NSERC | $87.5 |

| CIHR | $98.0 |

Source: Mid-term reports submitted by Competition 1 grantees