Prepared by:

SSHRC/NSERC Evaluation Division

PRA Inc.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 2020

Cat. No. CR22-110/2020E-PDF

978-0-660-35639-6

PDF document

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

About the Funding Programs

Launched in 2008, the Canada Excellence Research Chairs (CERC) program supports Canadian universities in research and innovation with an award of $10 million over seven years to facilitate the attraction of world-class researchers to become CERC chairholders in areas of strategic importance to Canada. These chairholders build core teams at their host institution for the purpose of developing and expanding research programs in their respective areas of study.

Launched in 2017, the Canada 150 Research Chairs (C150) program aimed to attract top-tier, internationally based scholars and researchers to Canada (including Canadian expatriates) in order to commemorate Canada’s 150th anniversary. Open to researchers of all disciplines and career stages, the program offered a one-time investment to Canadian institutions of either $350,000 or $1 million per year for seven years with the ultimate goal being to further Canada’s reputation as a global centre of research excellence.

About the Evaluation

The scope of the evaluation covers the period from 2013-14 to 2017-18 for the CERC program, and from 2017-18 to 2018-19 for the C150 program. The purpose of this evaluation is to provide program Management and Steering Committee members with key information on the relevance and performance of the CERC and C150 programs. Given that C150 chairholder positions were awarded in 2018 and 2019 (overlapping with this evaluation), the assessment of this program was more limited in scope than that of CERC. We examined both programs’ relevance; contributions to attracting world-class researchers to Canada; and aspects of design, delivery and efficiency. The evaluation of the CERC program additionally considered outcomes of interest, including an assessment of the extent to which CERC contributed to building and sustaining research capacity in Canada within the strategic areas identified by the federal government.

The evaluation of the CERC and C150 programs features multiple lines of evidence, including a review of program documents and key literature, a review of files and administrative data, a bibliometric analysis, case studies of a sample of CERCs from the first cohort, a survey with CERC core team members and key informant interviews. Interviews were conducted with CERC chairholders (those not included in case studies, those who left before the end of their term, and active Competition 2 chairholders), C150 chairholders (including those who declined the award), vice-presidents (VPs) of research, and selection committee and review panel members.

Primary limitations of the data were the small sample of chairholders (N = 26 CERC chairholders from Competitions 1 and 2; N = 25 C150 chairholders), which precluded the use of inferential statistics in the context of certain analyses. Despite some missing data associated with the survey of core team members and CERC annual reports, we are confident in our ability to report major trends from the quantitative data—particularly given our ability to triangulate these quantitative findings with other lines of evidence.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Evaluation Question 1: To what extent do the CERC and C150 programs continue to address a unique need?

Key findings suggest that CERC and C150, namely due to their prestige and value, are unique in their ability to attract and support world-class international researchers in building research capacity within Canada. These programs represent a specific niche in federal funding programs. Despite a few institutional representatives expressing concern about the tension created among faculty as a result of the disproportionately high level of funding issued to a single research team, most stakeholders shared positive feedback about CERC: they commonly expressed that the program was necessary to attract the calibre of researcher in question. Overall, the perception among stakeholders, combined with the influx of world-class researchers into Canada and their noted productivity thus far, is that Canada should continue investing in scientific research through CERC and C150. Other countries are making large investments in research; therefore, in order to remain globally competitive, Canada needs to continue offering awards of similar calibre.

Evaluation Question 2: To what extent have the CERC and C150 programs attracted world-class researchers to Canada?

Through bibliometric analysis, this evaluation has determined that the CERC and C150 programs have indeed been successful in attracting world-class researchers to Canada. In turn, the reputation and innovative research of these chairholders has been cited as a main factor in attracting faculty and highly qualified personnel (HQP) to core teams, and has also facilitated the forming of partnerships and collaborations both nationally and internationally.

Evaluation Question 3: To what extent have the CERCs contributed to enhanced and sustainable research capacity at Canadian universities in areas of strategic importance identified by the federal government?

In the context of this evaluation, sustainability is operationalized as the growth and retention of the core team, partnerships and collaborations built through the CERC, and the continued prolific production of quality research outputs. An in-depth assessment of sustainability capturing longer-term impacts will likely only be possible in the context of the next CERC evaluation. However, it was still possible to gauge sustainability in a preliminary way in this evaluation by examining chairholders’ and core team members’ intent to remain at their host institution and/or in Canada, as well as the perceived impact of the end of CERC funding on partnerships and collaborations.

The majority of chairholders perceive the CERC program to have had great influence on their ability to establish both national and international partnerships and collaborations, which in turn have been useful in leveraging additional sources of funding and laboratory resources. Bibliometric analysis has found that CERC host institutions have seen significant increases in annual publications in the research area of the CERC as a direct result of the chairholders’ output (approximately an additional 10 articles per year or a 13.3% increase). The CERC host institutions are also well above their comparator Canadian and foreign institutions in annual publications. Although the measured increase in publications from pre- to post-award for individual chairholders is modest rather than pronounced (and commensurate with the relative increase observed among Canada Research Chairs [CRCs]), these figures are likely an underestimate given that (1) CERC-funded research outputs (even from Competition 1 CERCs) are still emerging and (2) these data only capture the chairholder’s publications and not those of the CERC team as a whole. Finally, publication volume captured through bibliometric data is but one of many indices of research capacity and contributions.

Although it might be of interest to examine how the CERC program compares to other tri-agency programs with respect to cost per publication, such comparisons would likely result in misleading conclusions. Recall that a CERC is defined not only by the chairholder’s contributions, but more holistically by the core team and research program that is built at the host institution, as well as the larger research networks that the CERC team establishes. Qualitative data from the current evaluation suggest that the CERC program has resulted in increased research capacity at host institutions and has greatly influenced the career trajectories of team members, thus contributing to a range of successes that extend beyond the accomplishments of the chairholder alone. Although the broader, cascading impacts of the program could not be quantified, it is important to keep these larger contributions in mind when comparing the CERC program to other programs that may, by design, have a narrower reach.

Recommendation 1 (CERC): Continue funding the CERC program conditional on future evidence of sustainability and contingent on the government maintaining its priority to remain globally competitive by attracting world-class researchers to Canada in order to build capacity in areas of strategic importance to our social and economic landscape.

Importantly, CERCs reported that their partnerships and collaborations are providing linkages primarily with other academic institutions rather than other organizations in the private and public sector. Additionally, CERCs reported a low prevalence of research outputs tailored to government and public policy contexts, primarily citing research outputs tailored to academic audiences (i.e., scholarly refereed journals and conference proceedings). The implication is that CERCs may not be reaching wider audiences beyond academia—an expected intermediate outcome as per the program’s logic model. Although this may in part be due to the longer time period required for government and public policy uptake, this evaluation indicates that increasing the visibility of the chairholders and their research would be beneficial, in turn introducing potential opportunities to establish linkages in other sectors and disseminate research to non-academic audiences, including government decision-makers.

Recommendation 2 (CERC): Develop strategies to further promote the CERC program as a whole and encourage institutions to enhance their knowledge dissemination and external communication strategies related to CERC teams.

In terms of sustaining research capacity in Canada, the majority of CERC chairholders (nearly 80%) plan to remain at their host institution following their CERC term; in addition, 50% of core team members surveyed indicated a desire to remain in Canada after the CERC term. CERC chairholders’ desire to stay at their host institutions is influenced by a number of factors, including the success and strength of the research program they have created, the investment in infrastructure they have made at the institution, the support and level of commitment to sustainability received from their host institution, and their ability to secure additional funding at the end of the CERC term. Host institutions report growth through the CERC program—namely evidenced by the CERC’s role in the development of new research programs, the creation of new faculty positions, the promotion of research more broadly and the development of new technologies. An additional key concern held by the majority of chairholders was in the overall sustainability of the CERC program and the potential impact that the end of CERC funding might have on their ability to sustain the collaborations and partnerships they have fostered through their position. The degree to which the program truly leads to the creation of sustainable research capacity should be more evident at the time of the next evaluation, at which time over five years will have elapsed from the end of the Competition 1 CERC terms.

Evaluation Question 4: To what extent are the design and delivery of the CERC and C150 programs effective and cost-efficient?

Several key strengths of the programs were noted by both chairholders and institutional representatives, including the flexibility in the use of CERC funds, the value and prestige of the CERC and C150 awards and the selection of the CERCs in strategic areas of research for Canada. However, interviews with chairholders and institutions alike revealed there was sometimes misalignment of expectations, largely a product of proposals and sustainability plans that lacked concrete goals and commitments.

Recommendation 3 (CERC): Ensure that all CERC institutional commitments and sustainability plans are concrete, transparent, and developed as early as possible (beginning at the application stage) so as to ensure that chairholder and institutional commitments are fulfilled. This should include sharing or creating the opportunities to share promising practices for CERC sustainability among host institutions and CERCs (e.g., forums) and requiring concrete commitments by institutions with regular follow-ups to ensure commitments are honoured.

Other concerns raised by chairholders and other key informants surrounded the length of the CERC term; that is, the number of years available to spend the $10 million award. Beyond the fact that the CERC is not renewable, several chairholders indicated that the seven-year term was too short a period to build such a large research program. It was also noted that research needs and timelines vary according to research area. Delays in getting research labs running at the start of the CERC terms was a challenge, especially when considering the high level of progress that is expected with this kind of program. Extending the terms or having a more explicitly defined tapering-off period would be helpful. Although automatic extensions of one year are provided and the Terms and Conditions of the award allow for the possibility of an additional extension with proper justification, the latter option was not universally understood among chairholders and institutions.

Recommendation 4 (CERC): Provide more clarity and transparency to institutions and chairholders at the outset and throughout the term of the award about extension possibilities.

The timeframe for the CERC application and nomination process was considered too lengthy and onerous, which ultimately led to the loss of desirable candidates in favour of other job opportunities. In addition to the poor timing of the competition (i.e., over the summer while many people were away and difficult to reach), the primary issue with the C150 competition was the fact that its timeline was too compressed, which created a number of logistical issues and ultimately resulted in candidates declining the potential nomination due to the timeframe.

Recommendation 5 (CERC): Further streamline the chairholder recruitment and review process with a view to balance the need to thoroughly vet nominees and their research programs with the need to remain competitive and avoid “losing good candidates.”

CERC chairholders from the first and second competitions are relatively homogeneous, generally not identifying with any of the four designated groups (i.e., women, persons with disabilities, Indigenous Peoples and members of visible minorities). However, several advances in the design of the CERC program (that were also applied to the C150 program) have been made since the first two CERC competitions to increase the level of equity and diversity within the program. Namely, the introduction of formal equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) requirements in the selection criteria and institutional recruitment process, the inclusion of a detailed equity plan and the inclusion of an individual with EDI-related expertise on peer review panels. These changes to the recruitment and selection processes in the latest CERC and C150 competitions have resulted in a more diverse group of chairholders and core team members in terms of an increased representation of women and visible minorities among awardees.

Recommendation 6 (CERC/C150): Continue to encourage proactive consideration of EDI in recruitment and selection processes for CERC chairholders and core team members through mechanisms such as additional training on EDI best practices and unconscious biases.

Despite advances over the last few years, there are still a number of EDI implementation challenges, which in part pertain to the lack of clarity around EDI requirements and what recruitment targets should be applied across the various equity-seeking groups. Review panel members reported struggling with how to assess and weigh EDI considerations in the selection and review process. This was also a commonly perceived challenge of chairholders when recruiting core team members. In addition, review panel members expressed that the individual(s) invited to provide EDI-related advice was not used effectively within the peer review process. Finally, institutions lamented the overall lack of clarity regarding the required elements of an equity plan at the time of application.

Recommendation 7 (CERC/C150): Improve communication of EDI requirements to provide greater clarity on how and why EDI should be considered in the recruitment, application, and selection processes for the nominees, the institutional recruitment committees and the review panels. Additional tools and resources should also be provided to help institutions and chairholders further develop their understanding of the systemic barriers that impact individuals from underrepresented groups within the research ecosystem.

Performance Reporting

As the CERC and C150 are relatively new programs, reporting practices have continued to evolve over time. Indeed, a tri-agency working group was formed in 2016 to further refine annual reporting templates. Although quantitative data extracted from annual reports were sufficient to support the evaluation of the program, the formulation and structure of key questions were often modified from year to year, which in many instances precluded longitudinal analysis. Additionally, based on wide variability in responses to certain items on the annual report combined with informal discussions with CERC chairholders and their administrative staff, there appeared to be a lack of universally applied definitions for key constructs (i.e., partnerships vs. collaborations; core team member; “providing expert advice”). Finally, there was a general perception by chairholders and institutional representatives that the annual reporting requirements were fairly onerous and lengthy, and that not all collected information was examined.

Recommendation 8 (CERC/C150): Revise the institutional and recipient reporting strategy, as well as the program protocol for reviewing the collected information through the following:

(1) Clearly define key constructs on the reporting template itself to ensure a common understanding among respondents (e.g., partner vs. collaborator, core team member, etc.); (2) Clearly identify portions of the annual reports that should be reviewed promptly by Tri-agency Institutional Programs Secretariat (TIPS) staff (e.g., issues, obstacles, suggestions for improvement) to ensure timely follow-ups and check-ins as needed.

1.0 Introduction

This report presents key findings, conclusions and recommendations from the 2018-19 evaluation of two tri-agency funding programs: Canada Excellence Research Chairs (CERC) and Canada 150 Research Chairs (C150).

1.1 Evaluation background and purpose

The CERC program supports Canadian universities in research and innovation with an award of $10 million over seven years, facilitating the attraction of world-class researchers to become CERC chairholders in areas of strategic importance to Canada. Institutions must ensure 100% in matching funds over the term of the award (excluding tri-agency and CFI sources). Chairholders build core teams at their Canadian host institutions for the purpose of developing and expanding research programs in their respective areas of study.

The C150 program was intended to commemorate Canada’s 150th anniversary and offered a one-time investment to Canadian institutions of either $350,000 or $1 million per year for seven years with an aim to attract top-tier, internationally based scholars and researchers (including Canadian expatriates) from all disciplines and career stages. With the objective of further strengthening Canada’s research capacity and enhancing its reputation as a global centre of research excellence, the program was developed to build on the gains and contributions of other tri-agency programs including CERC, Canada Research Chairs (CRC) and Canada First Research Excellence Fund (CFREF).

The purpose of this evaluation is to provide program Management and Steering Committee members with key information on the relevance and performance of the CERC and C150 programs. Aspects of the program design, delivery and cost-efficiency are also covered. The CERC and C150 evaluations have been conducted in compliance with the requirements stipulated in the Treasury Board’s Policy on Results, with respect to Section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act, and aligned with the federal government’s commitment to equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI). Please note that although the EDI requirements were embedded within the C150 competition, these policies were not formally applied within the CERC program until the third and most recent competition. Although Competition 3 of the CERC program is discussed to contextualize recent advances in EDI and other processes, it is not formally included in the current evaluation.

1.2 Evaluation scope and questions

The scope of the evaluation covers the period from 2013-14 to 2017-18 for the CERC program, and from 2017-18 to 2018-19 for the C150 program so as to maximize the amount of information available on the latter. The evaluation of C150 was undertaken in tandem with the evaluation of CERC due to the level of commonality between the two programs. More specifically:

- given their similarly large disbursements, C150 was considered a good comparator to CERC in its potential for attracting world-class chairholders;

- the design of the recruitment process for both programs targets international candidates;

- it was deemed more appropriate to evaluate the C150 program with the CERC program in 2018-19, and subsequently five years from now (instead of evaluating C150 with the CRC program two years from now, as was the original plan). Evaluating C150 and CERC in tandem would not only provide early findings on the attraction of world-class researchers and lessons learned related to design and delivery, it would also offer an opportunity to better capture the achievement of program outcomes (and introduce potential adjustments) before the C150 funding period ends;

- finally, given the infancy of C150 and the potential for targeting both CERC and C150 chairholders during the same data collection effort, it was deemed most efficient to evaluate the two programs in tandem rather than evaluate the C150 program separately.

Given that C150 chairholder positions were awarded in 2018 and 2019 (overlapping with this evaluation), the assessment of this program was more limited in scope relative to CERC. The evaluation examined both programs’ relevance in the context of the current national and international research climate; contributions to attracting world-class researchers to Canada; and aspects of design, delivery and efficiency. The evaluation of the CERC program additionally included an assessment of outcomes; namely, the extent to which the program contributed to building and sustaining research capacity in Canada within the strategic areas identified by the federal government. This evaluation included only a narrow selection of CERC program outcomes so as to avoid duplication with the previous evaluation of the program conducted in 2013-14.

The current evaluation was designed to address the following four questions:

- To what extent do the CERC and C150 programs address (or continue to address) a unique need?

- To what extent have the CERC and C150 programs attracted world-class researchers to Canada?

- To what extent have the CERC chairholders contributed to enhanced and sustainable research capacity at Canadian universities in areas of strategic importance identified by the federal government?

- To what extent are the design and delivery of the CERC and C150 programs effective and cost-efficient?

The complete evaluation matrix that aligns the evaluation questions to indicators and data sources appears in Appendix B.

1.3 Evaluation methodology

SSHRC evaluators and an evaluation consulting firm (PRA Inc.) collaborated to design and implement this evaluation. The process was guided by an evaluation advisory committee comprised of representatives from the SSHRC Evaluation Division, the Tri-agency Institutional Programs Secretariat (TIPS), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI).

The evaluation of the CERC and C150 programs features multiple lines of evidence, including a review of program documents and key literature, a review of files and administrative data, interviews with key informants (n = 51), case studies of CERCs awarded during the first competition (n = 9), a web based survey with telephone follow-up of CERC core team members (n = 562, response rate = 37%) and a bibliometric analysis.

The bibliometric study, performed by Science-Metrix and designed in consultation with SSHRC, had two main foci: (1) to measure the CERC and C150 programs’ ability to attract world-class researchers to Canada; and (2) to measure contributions of CERCs to Canadian institutions with respect to research output and impact. Contributions to research output and impact were based on a number of bibliometric indicators yielded for the period following respective award dates.

In terms of measuring the programs’ ability to attract world-class researchers, several bibliometric indicators were analyzed over the 10-year period pre-award relative to a number of comparison groups, including unsuccessful applicants to the programs and matched groups of Canada Research Chairs (CRCs). Although the CERC program issues relatively fewer awards that are larger in value than the CRC program, both programs target established researchers who are acknowledged to be world leaders in their respective fields and include the recruitment of internationally based researchers. As such, the latter was identified as a reasonable and valid comparator.

This evaluation’s key methodological challenges and corresponding mitigating strategies included the following:

- Reporting practices associated with CERC annual reports have not been consistent over time. Specifically, the formulation and structure of key questions were often modified from year to year, which in many instances precluded longitudinal analysis. This issue was compounded by some missing data in the annual reports, either because chairholders or institutions opted not to answer certain questions or, because under exceptional circumstances identified on an ad hoc basis, a chairholder was not required to submit an annual report in a particular year. Moreover, the nature of the reporting template is structured in such a way that aggregate values of certain fields (e.g., number of core team members, number of partnerships) could not be determined by summing across years given the possibility of double-counting. As such, it was typically only possible to determine the median for a construct of interest at a given point in time; note that we generally opted to report median over mean as a measure of central tendency to minimize the impact of distributional outliers. Finally, the default entry of “0” in later reporting templates resulted in an inability to determine whether “0” values referred to missing data or to the genuine absence of activity. Despite limitations associated with CERC reporting templates and the resulting administrative data for CERC, we were nonetheless able to determine major trends and triangulate findings with alternative lines of evidence to confirm their validity.

It should be noted that a tri-agency working group was formed in February 2016 to review the logic model (LM) and performance measurement strategy (PMS) of CERC in response to the recommendations of the fifth-year program evaluation. In the context of this working group, TIPS policy and CERC program teams began to redesign the annual report templates for chairholders and institutions, which received final approval by the Associate VP of TIPS in January 2018. Notably, these redesigned templates were used for the 2016-17 and 2017-18 reporting periods and already address many of the reporting issues identified above.

- Based on wide variability in some of the quantitative data associated with annual reports, combined with informal discussions with CERC chairholders and their administrative staff, there appeared to be a lack of universally applied definitions for certain key constructs. For example, when the evaluation team requested complete CERC core team member lists from chairholders for the purpose of constructing a survey sample frame, it became clear that the definition of “core team member” varied from chairholder to chairholder. Regarding the annual reports, we strongly suspect that respondents have inconsistent definitions for terms like “partnership” and “collaboration” (e.g., the number of collaborators and partners reported by chairholders ranged from 1 to 160 and from 1 to 50, respectively). To address this concern, major trends are often reported over specific numbers where validity is questionable, coupled with triangulation with other available lines of evidence.

- Complete lists of names and contact information for the CERC core team membership are not currently collected by TIPS. Therefore, as indicated above, the SSHRC Evaluation Division contacted individual chairholders in an attempt to obtain a representative survey sample frame of current and former CERC core team members. In total, 23 of the 26 CERCs provided such lists. Notwithstanding missing data, all CERC core teams had at least some members included in the overall sample given the combination of these data with the sample of core team members who consented to be contacted for evaluation purposes upon completing their self-identification form in June 2018 (a data collection effort managed by TIPS). The impact of missing data on the evaluation findings is expected to be minimal given the acceptable response rate to the survey of 37% (a rate typical of similar evaluations) and representation from each CERC team among the respondent pool.

- Due to the small number of chairholders in the samples (for both CERC [N=26] and C150 [N=24]), it was not always possible to conduct inferential statistical tests. In the CERC administrative data review and in some bibliometric analyses, only descriptive data were presented to illustrate group differences (e.g., number of CERCs in different priority areas, representation among EDI groups, etc.). Furthermore, certain sub-groups of survey respondents and chairholders could not be disaggregated and analyzed separately given the small number of individuals falling into those categories and because of the potential for identification (e.g., membership to EDI groups, host institution, etc.). However, with the presentation of descriptive statistics and triangulation with other lines of evidence, we can be reasonably confident in the validity of the reported conclusions.

- Although we compare CERCs, C150s and CRCs in the bibliometric analysis, it should be noted that it was only possible to capture the research productivity of the CERC chairholder and not members of the CERC core team. As such, the bibliometric output is an underestimate of the true productivity of the CERC team. That said, it is reasonable to assume that, with respect to peer reviewed publications, the majority of core team members would list the chairholder as a co-author. Accordingly, bibliometric data are still considered a reasonable indicator of publication output.

2.0 Relevance

2.1 External factors influencing the need for CERC and C150 programs

Summary of Findings: There is a perceived need for Canada to continue investing in research through programs such as the CERC and the C150 in order to remain globally competitive. Other countries are making large investments in research: as a result, there is a perceived need for Canada to actively continue to attract world-class researchers by offering awards of competitively high value and prestige.

Canada is generally regarded as a strong research country, but over the last decade has begun to lag behind certain countries in research and development (R&D) investment as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), research output (e.g., volume of publications in peer-reviewed journals) and research impact (e.g., Average Relative Citation [ARC] score). Emerging countries such as China and India are investing more in research than Canada and a number of other traditionally strong research countries, which is resulting in increased global competitiveness with respect to research output, research quality and the attraction of researchers (Advisory Panel on Federal Support for Fundamental Science, 2017; Council of Canadian Academies, 2018; Government of Canada, 2012). In this context, where countries are investing considerable funding in research, interview and case study findings with institutional representatives at Canadian host universities (e.g., representative from the university research office, dean of faculty associated with the CERC) suggest that the international competitiveness for top talent both within academia and industry speaks to the need and relevance of the CERC and C150 programs.

Additionally, interview and case study findings strongly indicate that recent political changes in the international context have provided an opportunity for Canada to attract world-class researchers. The primary factors articulated by stakeholders include the Trump presidency in the US and Brexit in the UK—two political situations that are resulting in a “brain drain” from those countries and the desire among some researchers to relocate to other countries to pursue their work, with Canada being a strong and viable option.

2.2 Niche of CERC and C150 programs in Canada

Summary of Findings: The CERC and C150 programs target a specific niche relative to other federal programs aimed at building research capacity, with both programs aiming to attract top-tier researchers worldwide. Additionally, CERC and C150 are perceived as complementary to or to have synergies with other federal programs, particularly CFI programs and the CFREF program.

Filling a similar niche, the CERC and C150 programs are uniquely positioned to enhance Canada’s status as a world leader in research. Key informant interviews strongly support the view that there are no other funding initiatives in Canada that specifically target and support world-class international researchers and their teams to establish ambitious research programs at Canadian universities. There was general consensus among key informants that the main factors attracting world-class researchers are the level of funding of the CERC and C150 programs and the opportunity to conduct innovative research.

In addition to the CERC and C150 programs, Canadian institutions can benefit from a number of funding opportunities, including the CRC program, the CFREF program, and awards from the CFI. Overall, key informants agreed that the CERC and C150 programs are unique although complementary to other sources of funding such as the CFREF program and CFI programs.

The CERC program is unique

The multiple funding opportunities directed at Canadian institutions have been designed to fill different roles. While the CERC, C150 and CRC programs are institutional programs that help support specific researchers and their research programs, CFREF is an institutional multi-year operating grant. CFI, on the other hand, provides funding for research infrastructure (Advisory Panel on Federal Support for Fundamental Science, 2017).

CERC vs. C150. The emphasis with CERC is on building sustainable research capacity in the area of the CERC at the host university (including training a strong core team), establishing networks and collaborations and providing expert advice to sectors outside of academia. Contrary to CERC, which entails a lengthy multi-stage application process (including both institutional and chairholder applications and review processes), a “rapid response” process was used to facilitate the recruitment of esteemed researchers in the C150 competition—primarily due to the one-time only C150 competition intended to mark the celebration of Canada’s 150th anniversary. In addition, in contrast to CERC’s focus on recruiting established researchers, the C150 program accepted applications from exceptional researchers at all career stages. Finally, Competition 1 and Competition 2 CERCs are almost entirely from the natural or health sciences (aligned with the federal government’s Science and Technology [S&T] Strategy and associated priority areas of research), whereas C150 has greater breadth in its representation from all disciplines of research in the social sciences and humanities, natural sciences and engineering, and health and related life sciences.

CERC vs. CRC. CERC and CRC are currently the major ongoing sources of federal funding for researcher salary support in Canada. These two funding opportunities are often compared because of their similar focus on the attraction of world-class researchers (Advisory Panel on Federal Support for Fundamental Science, 2017; Goss Gilroy Inc., 2016; Science-Metrix, 2010, 2014). The two programs are often perceived as complementary and present many similarities (Goss Gilroy Inc., 2016; Science-Metrix, 2010, 2014). Specifically, both programs support Canada’s global reputation, relying on local or regional concentration of resources to foster specialization (Advisory Panel on Federal Support for Fundamental Science, 2017). Both CERC and CRC programs additionally allow Canadian institutions to create research opportunities both to retain Canadian researchers and attract outstanding international researchers (Tri-agency Institutional Programs Secretariat, 2014).

Beyond certain similarities in their overall mandates, the CRC and CERC programs differ in several respects. Aligning specifically with the strategic areas identified by the federal government, the CERC program was created to further support Canada’s increasing global reputation in research, and strengthen Canada’s ability to attract the world’s top researchers (Advisory Panel on Federal Support for Fundamental Science, 2017; Tri-agency Institutional Programs Secretariat, 2017a). At $10 million over seven years, the CERC award value is much larger than CRC’s award values of either $200,000 annually for seven years (Tier 1) or $100,000 annually for five years (Tier 2). The three consecutive CERC competitions resulted in 40 research chairs (29 awarded chairs from Competitions 1 and 2, and an additional eight awarded chairs [and three pending chairs] from Competition 3). In addition, the link to federal policies and priorities is very strong as the CERC program is guided by federal priorities in science, technology and innovation. The federal government thus determines the S&T priority areas for which these chairs should be awarded (Tri-agency Institutional Programs Secretariat, 2017a). In contrast to CERC, the CRC program awards a larger number of chairs, with a total of 2,285 chair positions allocated to eligible institutions and 1,836 active chairs as of June 2019. Priority areas for the CRC program are determined by individual institutions given that nominations must be aligned with the Strategic Research Plans (SRPs) of each institution (Government of Canada, 2018).

The CERC program has a more global talent emphasis than the CRC program. All CERC chairholders awarded thus far have come from abroad (Goss Gilroy Inc., 2016). Although the CRC program also aims to recruit international researchers, the 15-year CRC program evaluation showed that the percentage of international recruits was declining: whereas foreign nominees respectively accounted for 32% and 31% of new Tier 1 and Tier 2 nominees over the 2005-09 period, they represented only 13% and 15%, over the 2010-14 period. The CERC and C150 programs, aimed at international recruitment, have helped to address this issue.

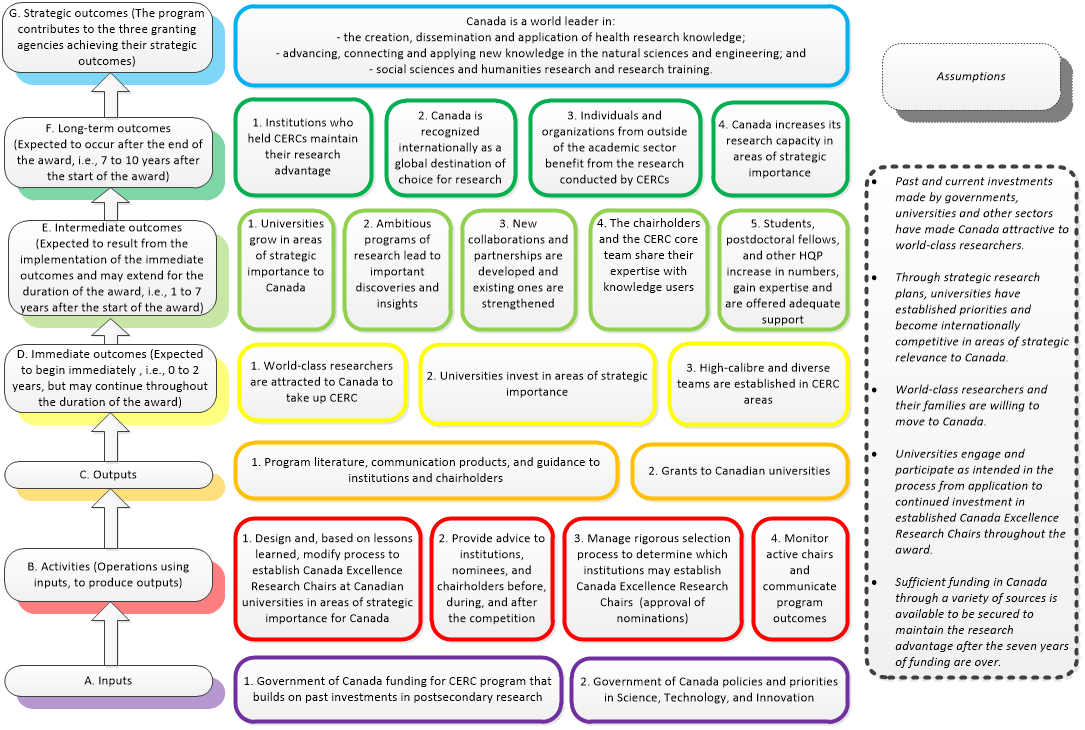

CERC vs. CFREF. The CFREF award emphasizes institutional specialization and encourages inter-institutional and international collaboration. Indeed, support for institutional initiatives, the creation of partnerships, and the creation of a research-inducing environment are some of the program’s main objectives (Advisory Panel on Federal Support for Fundamental Science, 2017; Tri-agency Institutional Programs Secretariat, 2017b). While the CERC program also aims to achieve these results, the focus is not on institutions, but on chairholders and their teams. As described in the CERC program’s logic model (see Appendix A), the attraction of world-class researchers and high-calibre teams (immediate outcomes) is expected to trigger the growth of universities in strategic areas (intermediate outcome) (Tri-agency Institutional Programs Secretariat, 2017a).

Research funding opportunities are complementary and synergistic

Despite the unique need addressed by CERC and C150, these programs are also complementary to and synergistic with other federal funding opportunities. Based on available data from annual reports, we know that at least half of the CERCs have reported CRCs among their core team members: this proportion is likely an underestimate given the fact that data on CRC participation was only collected in the 2014-15 fiscal year. Moreover, institutions often align their CERC and CFREF applications so that they are in similar research areas. About three-quarters (20 of the 26) of the CERC chairholders from the first two competitions are directly involved in about three-quarters (13 of the 18) of the CFREFs. Additionally, four of the CFREF initiatives are led by CERC chairholders.

By further enhancing and building upon Canada’s reputation as a global centre for science, research, and innovation excellence, the C150 program builds on the achievements made by the CRC and CERC programs for capacity development, and on the CFREF program in terms of global research leadership (Tri-agency Institutional Programs Secretariat, 2017c). Canadian institutions can benefit from the C150 program to extend an existing research area, but can also build a critical mass in a new area (Government of Canada, 2017).

Finally, CFI research infrastructure funds are also an important source of funding for the CERC teams. Nearly all active CERCs (85%) obtained infrastructure support at some point during their CERC term through the John R. Evans Leaders Fund (JELF) or Innovation Fund (IF) funding opportunities offered by CFI; six CERCs obtained CFI funding for more than one project.

3.0 Attracting world-class researchers to Canada

3.1 Calibre of CERC and C150 chairholders

Summary of Findings: The CERC and C150 programs have successfully attracted world-class researchers to Canada. Results of a bibliometric analysis demonstrate that CERC and C150 chairholders performed on par or better than matched control groups of Canadian and foreign CRCs in respective pre-award periods. Although all three programs attract some of the highest calibre researchers in the world, CERC and C150 chairholders are truly world-class by bibliometric standards. Notably, both the CERC and C150 chairholders are roughly comparable on the majority of bibliometric indicators, reflecting their similarly high calibre.

Successful CERC and C150 applicants are more prolific in terms of publication rates than unsuccessful applicants in the pre-award period

Overall, bibliometric analyses indicate that when a peer review committee involved in the chair selection process is faced with an almost uniformly high-performing pool of CERC and C150 candidates, field of study notwithstanding, committee members tend to select those with higher research outputs. Specifically, when comparing bibliometric indicators among successful and unsuccessful CERC and C150 candidates over the 10-year pre-award period, successful CERC and C150 candidates were more prolific than unsuccessful candidates based on publication rate (9.9 vs. 6.8 publications per year for the CERC program and 7.2 vs. 5.8 publications per year for the C150 program).

Scientific performance of CERC, C150, and CRC chairholders pre-award is above global levels

Bibliometric indicators revealed that CERCs, C150s, and respectively matched CRCs performed above global levels on a number of citation metrics over the 10-year period pre-award. Congruent with the intention of CERC and C150 to attract world-class researchers, chairholders associated with these programs performed either on par or better on a number of metrics than matched groups of foreign and Canadian CRCs (see Table 1 and Table 2). These findings indicate that, although all three programs attract some of the highest calibre researchers in the world, CERCs and C150s clearly distinguish themselves as world-class by bibliometric standards.

Table 1: Scientific performance of active CERC chairholders and matched foreign and Canadian CRC Tier 1 chairholders pre-award

| Metric |

CERC chairholders

(N = 26) |

Matched CRC1 chairholders (foreign)

(N = 26) |

Matched CRC1 chairholders (Canadian)

(N = 95) |

| Publications per year |

11.0* |

6.6 |

6.5 |

| Average of Relative Citations (ARC) |

2.64* |

2.03 |

2.02 |

| Highly Cited Publications (HCP)10% |

29.2%* |

22.4% |

21.8% |

| Highly Cited Publications (HCP)1% |

4.6% |

3.1% |

2.9% |

*Statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Source: Bibliometric analysis performed by Science-Metrix.

Table 2: Scientific performance of successful C150 applicants and matched foreign and Canadian CRC chairholders pre-award

| Metric |

Successful C150 applicants

(N = 24) |

Matched CRC chairholders (foreign)

(N = 24) |

Matched CRC chairholders (Canadian)

(N = 96) |

| Publications per year |

7.2* |

2.5 |

4.3 |

| Average of Relative Citations (ARC) |

2.61* |

2.05 |

2.23 |

| Highly Cited Publications (HCP)10% |

30.9% |

28.7% |

25.9% |

| Highly Cited Publications (HCP)1% |

6.2%* |

2.5% |

3.7% |

*Statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Source: Bibliometric analysis performed by Science-Metrix.

Comparing bibliometric standings of successful CERC and C150 chairholders indicates that both funding streams attracted candidates of roughly equal calibre, a perception that is generally echoed by institutional representatives participating in key informant interviews. Notable differences are only seen on two indicators: average yearly publication output and share of HCP papers. Specifically, recommended C150 candidates have a higher share of papers that fall among the very top cited publications in their field when compared with recommended CERC candidates (6.2% for C150s vs. 4.9% for CERCs). However, on average, recommended CERC candidates published about two more papers per year than C150s during the pre-award period.

3.2 Diversity of CERC and C150 chairholders

Summary of Findings: There is little diversity among the group of CERC chairholders from the first and second competitions, with the vast majority of grantees not self-identifying as belonging to one or more of the four designated groups: women, Indigenous Peoples, persons with disabilities and members of visible minorities. However, given changes to the program design whereby EDI requirements were embedded, the third CERC competition and the C150 competition have resulted in a significantly greater number of chairs awarded to individuals who self-identify as women and members of visible minorities, with over 50% of successful candidates from each of these competitions self-identifying as women and over 20% self-identifying as a member of a visible minority. Individuals self-identifying as persons with disabilities and/or Indigenous Peoples within the group of awardees remains minimal.

Within the group of CERC chairholders from Competitions 1 and 2, there was a lack of representation of individuals who self-identified as belonging to one or more of the four designated groups. Please note that data on the diversity of chairholders from the first two CERC competitions cannot be shared publicly given the low proportion of individuals self-identifying within each of the four designated groups.

Primarily in response to the almost exclusive male composition of chairholders from the first two CERC competitions, along with the recognition of the importance and benefits of EDI to achieving research excellence (i.e., through greater innovation and diversity in perspectives; Hewlett, Marshall, & Sherbin, 2013; SSHRC, 2019), multiple changes were introduced by TIPS in the third CERC competition and the C150 competition. Specifically, EDI requirements were formally incorporated into the selection criteria and institutional recruitment process (Government of Canada, 2016b, 2017). As a result, the third CERC competition (currently n = 8) and the C150 competition resulted in significantly increased diversity among chairholders, with over 50% of chairholders from each of these competitions self-identifying as women and over 20% of C150 chairholders and Competition 3 CERC chairholders self-identifying as a member of a visible minority.

The significant increase in the diversity of chairholders that results when EDI is embedded in program requirements underscores the need to ensure EDI remains a strategic, sustainable and systemic consideration in both the CERC and C150 programs. Although the C150 competition technically attained the general labour force representation of 4%, there remains underrepresentation with respect to persons with disabilities. Again, specific proportions are not available given the small sample size so as to protect the privacy of chairholders.

There are a number of potential explanations for the low representation of persons with disabilities among CERC and C150 chairholders and the low representation of Indigenous Peoples among CERC chairholders. Key informants commonly made the observation that underrepresentation of CERC and C150 chairholders among these two designated groups is likely influenced by the small pool of researchers self-identifying as such, both in Canada and internationally. Indeed, across all disciplines, individuals self-identifying as Indigenous remain significantly underrepresented in academia, comprising only 1.4% of university professors in Canada (contrasted with almost 4% in the labour force) (Canadian Association of University Teachers; CAUT, 2018). Based on representation alone, this is an issue worth greater attention and discussion. Available evidence suggests a similar underrepresentation of persons with a disability in academia. According to the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY), subsequently linked to tax information, individuals diagnosed with a physical and mental health condition in their youth were between 17 and 29 percentage points less likely to enroll in postsecondary education compared to a control group of individuals not diagnosed with one or more of these conditions (Arim & Frennette, 2019).

The possibility of underrepresentation aside, the available data may be underestimating the actual prevalence of researchers in these two designated groups. EDI data collection efforts in general are still in their infancy. Although Statistics Canada is currently developing improved reporting practices to more accurately capture breadth in the measurement of the four designated groups, existing data may actually be an underestimate of the actual level of diversity among academics (and other populations). Regardless of reporting refinements, individuals may simply be reluctant to self-report membership to these two specific designated groups for varied reasons—consider, for example, the stigma that might be associated with having an invisible disability (e.g., a mental health diagnosis) in a highly competitive environment that values high achievement and intellectual prowess (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2019), or cases involving ambiguity around one’s Indigenous identity (e.g., being Indigenous to one’s country of origin, but not Indigenous to Canada). In sum, it is plausible that institutional recruitment processes for CERC and C150 do not adequately capture the true extent of self-identification within these two groups.

3.3 CERC core team members

Summary of Findings: The integral factors encouraging faculty and HQP to join the CERC core team are the ability to conduct innovative research; the opportunity to increase their skills; the reputation and calibre of the chairholder; and access to state-of-the-art infrastructure. With a median team size of nearly 30, the CERC program appears to be building capacity at host institutions, with core team members drawn fairly evenly from both Canada and abroad.

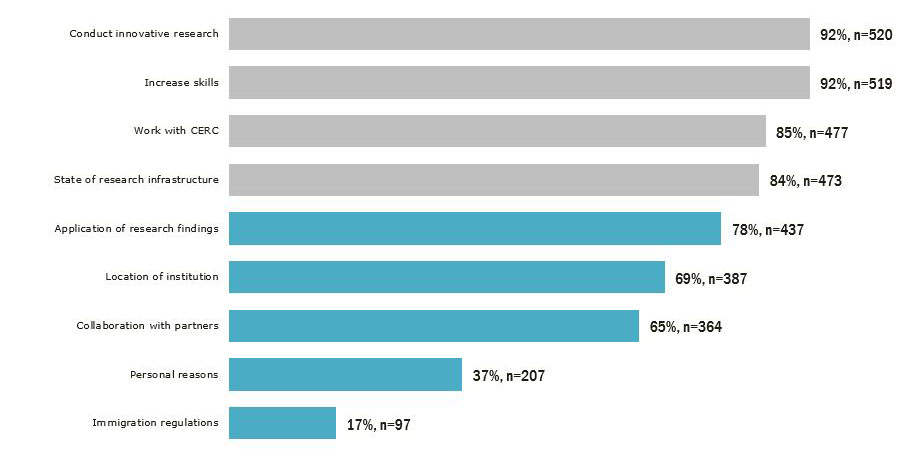

Opportunity to work with CERC chairholder is one of the primary reasons for faculty and HQP to join the CERC core teams

Faculty or highly qualified personnel (HQP: undergraduates, graduates, postdoctoral fellows, research technicians, research associates and other technical or research personnel) are recruited to work with the CERC chairholder as CERC core team members. As evidenced by the survey results presented in Figure 1, in addition to being afforded the opportunity to conduct innovative research and hone their skills, the opportunity to work with the chairholder and to have access to state-of-the-art infrastructure were the primary reasons for which faculty and HQP opted to join the CERC team. These findings were supported by interviews conducted with faculty and HQP included in the case studies, although both former and current team members more consistently indicated that it was primarily the reputation and calibre of the chairholder and interest in the work being undertaken by the CERC that were the key factors attracting them to the CERC core team.

Figure 1: Factors that encouraged core team members to join the CERC core teams

Conducting innovative research, increasing skills and opportunity to work with the CERC encouraged faculty and HQP to join the CERC core team

Source: Survey of CERC core team members

Figure 1 long description

Figure 1: Factors that encouraged core team members to join the CERC core teams

Conducting innovative research, increasing skills and opportunity to work with the CERC encouraged faculty and HQP to join the CERC core team

| Factor |

Percentage |

Frequency |

| Immigration regulations |

17% |

97 |

| Personal reasons |

37% |

207 |

| Collaboration with partners |

65% |

364 |

| Location of institution |

69% |

387 |

| Application of research findings |

78% |

437 |

| State of research infrastructure |

84% |

473 |

| Work with CERC |

85% |

477 |

| Increase skills |

92% |

519 |

| Conduct innovative research |

92% |

520 |

Source: Survey of CERC core team members

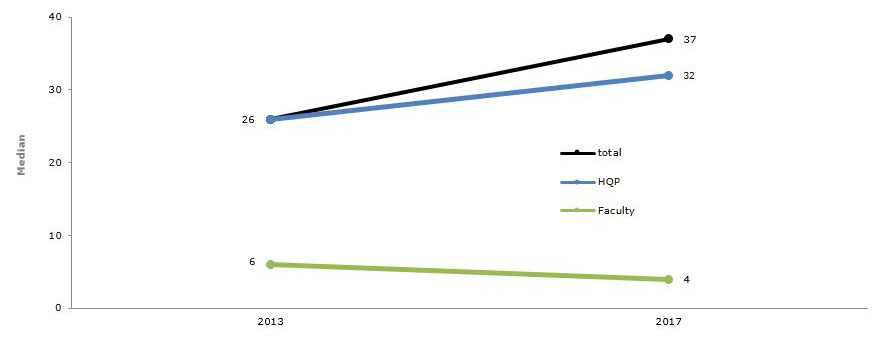

Composition of CERC core teams varies by member type (faculty and HQP) and priority area

Based on the five-year period between 2013 and 2017, the median CERC team consists of 29 core members in a given year (ranging between eight and 202 core team members per CERC). When examining faculty separately, only data between 2014 and 2017 were available, and show a median team count of four (range = 1 to 75). When considering HQP separately, the median team count is 27 personnel (range = 7 to 131). Upon further disaggregating the different groups of HQP (i.e., undergraduate students, master’s students, PhD students, postdoctoral fellows, and other HQP, respectively), results indicate a fairly even split between these groups on core teams, with a median number of approximately five personnel per HQP grouping.

Given the wide range of reported core team personnel in annual reports, core team size and distribution were also analyzed by research priority area (as aligned with federal government priorities) to determine if area of research might be a factor influencing the size of a research team. Table 3 illustrates that the priority area associated with the largest CERC teams is environmental sciences and technologies (EST), showing a median team count of 46 members, in comparison to the median team count of 23.5 members on a CERC team in a health-related area.

Table 3: Total median team size, split by priority area

| Priority Area |

n CERCs |

Median number of faculty |

Median number of HQP |

Median number of total personnel |

| Environmental sciences and technologies |

5 |

7.50 |

40.00 |

46.00 |

| Natural resources and energy |

5 |

9.00 |

28.00 |

31.50 |

| Information and communications technologies |

6 |

4.50 |

26.75 |

30.50 |

| Health and related life sciences and technologies |

8 |

3.00 |

20.50 |

23.50 |

| Other (“open” priority areas; e.g., automotive industry) |

2 |

4.50 |

13.75 |

18.25 |

Source: Statement of account annual reports 2013-17

Almost half of the core team members surveyed (46%; n = 257) indicated they were already at the CERC host institution upon joining the core team. Though not surprising, faculty (59%, n = 56) were more likely than HQP (43%, n = 199) to have already been based at the host institution before joining the CERC core team. Of those core team members who came from a different institution, just under a third came from another institution in Canada (29%; n = 72) and just under a third came from Europe (32%; n = 80). The remaining were primarily based in the United States (13%; n = 33), Asia (12%; n = 31) and South America (8%; n = 20). Similar proportions were generally evident when disaggregating faculty and HQP, with one exception: a higher proportion of faculty versus HQP came from an institution in the United States (29% vs. 11%).

3.4 Diversity of CERC core team members

Summary of Findings: Half of CERC core team members self-identify as belonging to one or more of the four designated groups, with greater diversity evident among HQP than among faculty. Similar to the most recent chairholder profiles (Competition 3), there is diversity with respect to gender and visible minorities among CERC team members, with roughly one-third self-identifying as a woman and almost one-fifth self-identifying as a member of a visible minority. However, as was the case with chairholders, lack of diversity among CERC teams is evident with respect to the recruitment of persons with disabilities and Indigenous Peoples.

According to survey data, approximately half of the CERC core team members self-identify as belonging to one or more of the four designated groups (45%, n = 252), as shown in Figure 2. Just over one-third of core team members self-identified as a woman (34%; n = 190), with a higher proportion of women represented among the HQP group (38%, n = 168) compared to the faculty group (20%, n = 19). Just under one-fifth of core team members self-identified as a member of a visible minority (17%; n = 95), also with a greater proportion of HQP (20%; n = 85) than faculty (8%; n = 7) self-identifying as such. Of the 17% of survey respondents that self-identified as a member of a visible minority, about a third (42%; n = 40) self-identified as Asian, followed by less than one-quarter who self-identified as Middle Eastern (16%; n = 15).

Similar to results related to CERC chairholders, a very small number of core team members self-identified as a person with disabilities (2%; n = 11) or as Indigenous (n < 5). As discussed above, chairholders and institutional representatives express difficulty in recruiting researchers who self-identify within these two designated groups, perceiving that there is a smaller pool of eligible candidates. Beyond evidence of underrepresentation of these two designated groups within the academic environment both in Canada and internationally (e.g., CAUT, 2018; Mohamed & Beagan, 2019; Staniland, Harris, & Pringle, 2019), there is also the possibility that underrepresentation is at least partially an artefact of the data: individuals may choose to not self-identify for a multitude of reasons (e.g., stigma) and the actual number of individuals within groups may in fact be higher than is currently suggested. Responses from some of the chairholders and institutional representatives signal a need for further training within the academic environment to ensure that the systemic barriers in the research ecosystem, the benefits of EDI within research (on teams and within research design), and the connection between increased EDI and increased research excellence (e.g., Hewlett et al., 2013; SSHRC, 2019) are well understood.

Figure 2: Self-identification of CERC core team members

About half of CERC core team members identify as belonging to at least one of the four designated groups

*Respondents self-identifying with at least one designated group is 45%, n = 252.

*Total does not add to 100% as respondents were able to self-identify with more than one group.

*In keeping with the Privacy Act, numbers lower than five were suppressed to protect the privacy of respondents.

Source: Survey of CERC core team members

Figure 2 long description

Figure 2: Self-identification of CERC core team members

About half of CERC core team members identify as belonging to at least one of the four designated groups

| Designated group |

Percentage |

Frequency |

| Prefer not to answer |

6% |

34 |

| Indigenous Peoples |

<5%* |

n<5 |

| Persons with disabilities |

2% |

11 |

| Visible minorities |

17% |

95 |

| Women |

34% |

190 |

| Do not identify with any of these groups |

49% |

276 |

*Respondents self-identifying with at least one designated group is 45%, n = 252.

*Total does not add to 100% as respondents were able to self-identify with more than one group.

*In keeping with the Privacy Act, numbers lower than five were suppressed to protect the privacy of respondents.

Source: Survey of CERC core team members

4.0 Enhanced research capacity at Canadian universities in strategic areas of importance to Canada

To reiterate, given the infancy of C150, any outcomes discussed with respect to enhanced research capacity (and sustainability) as a result of funding is restricted to the CERC program. In the context of this evaluation, enhanced research capacity is examined through the quantity and impact of a CERC’s research outputs and knowledge mobilization activities while at the host institution, the degree to which CERC program has facilitated the forging of collaborations and partnerships, and the institutional growth that the CERC has catalyzed (i.e., increase in faculty, HQP, programs, facilities, and/or linkages with other institutions that would not have otherwise occurred).

4.1 CERC chairholder performance since award

Summary of Findings: CERC chairholders have increased their publication output and international co-publication rates following their awards compared to their performance pre-award. Generally, increases in bibliometric indicators for CERC chairholders post-award were modest rather than pronounced; among other contributing factors, this is potentially due to the “recovery period” experienced following award date (underscored in the 2013-14 CERC evaluation). This general trend is mirrored among foreign Tier 1 CRCs. CERC host institutions have experienced significant increases in annual publication output in the research area of the CERC as a result of chairholder contributions. Specifically, host institutions performed substantially above their comparator Canadian and foreign institutions in annual publication rates (by approximately 10 articles per year or an absolute increase of 13.3%), with these leads disappearing when CERC-authored publications were omitted from the sample. These results indicate that the CERC program has a significant and positive impact on awardees and host institutions in terms of publication productivity and impact.

Chairholders show significant increases in bibliometric indicators pre- to post-award

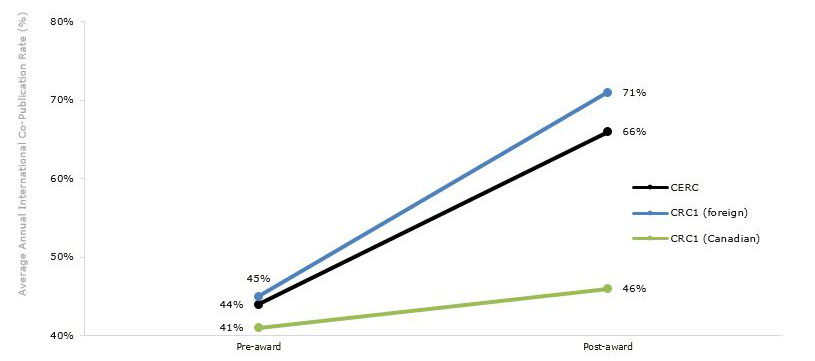

CERC chairholders demonstrated significant, positive increases in their publication productivity after the start of their award dates relative to their own performances over the 10-year pre-award period. This trend is also evident among matched Tier 1 CRCs, which, as outlined earlier, was deemed a valid comparison group given that both programs target established researchers who are acknowledged to be world leaders in their field. Specifically, both CERC and matched foreign and Canadian CRC1 chairholders significantly increased their average annual publication outputs from pre- to post-award, showing absolute increases of 22% (for CERCs), 28% (for foreign CRC1s) and 31% (for Canadian CRC1s; see Figure 3). Moreover, CERC and matched foreign CRC1 chairholders experienced significant increases in average annual international co-publication rates from pre- to post-award. Figure 4 displays the average rate at which CERCs and CRC1s publish research with international partners/collaborators, showing percent increases from pre- to post-award of 22% (for CERCs), 26% (for foreign CRC1s) and 4% (for Canadian CRC1s).

Figure 3: Average annual publication output of CERCs and CRC1s pre- and post-award

CERCs and CRC1s show positive increases in publication output from pre- to post-award

Source: Bibliometric analysis performed by Science-Metrix.

Figure 3 long description

Figure 3: Average annual publication output of CERCs and CRC1s pre- and post-award

CERCs and CRC1s show positive increases in publication output from pre- to post-award

| Group |

- |

Average papers per year |

| Established CERCs |

Pre-award |

11.6 |

| Post-award |

14.2 |

| CERC-matched foreign CRC1s |

Pre-award |

8.6 |

| Post-award |

11.0 |

| CERC-matched Canadian CRC1s |

Pre-award |

7.4 |

| Post-award |

9.7 |

Source: Bibliometric analysis performed by Science-Metrix.

Figure 4: International co-publication rates of CERCs and CRC1s pre- and post-award

CERC and foreign CRC1s show positive increases in international co-publication rates from pre- to post-award

Source: Bibliometric analysis performed by Science-Metrix.

Figure 4 long description

Figure 4: International co-publication rates of CERCs and CRC1s pre- and post-award

CERC and foreign CRC1s show positive increases in international co-publication rates from pre- to post-award

|

|

Average papers per researcher per year |

International co-publications rate |

| Established CERCs |

Pre-award |

11.6 |

44% |

| Post-award |

14.2 |

66% |

| CERC-matched foreign CRC1s |

Pre-award |

8.6 |

45% |

| Post-award |

11.0 |

71% |

| CERC-matched Canadian CRC1s |

Pre-award |

7.4 |

41% |

| Post-award |

9.7 |

46% |

Source: Bibliometric analysis performed by Science-Metrix.

Bibliometric analyses were also conducted to determine the respective impact of the research produced by CERCs and CRC1s. Mirroring trends observed among Tier 1 CRCs, increases in HCP indicators for CERC chairholders post-award were modest rather than pronounced. In the instance of the ARC, a very slight decrease was observed among CERCs and foreign CRC1s (see Table 4). However, given the sensitivity of the CFREF to distributional outliers, some bibliometricians recommend greater reliance on the HCP as the latter is year- and field-normalized (Nature Index; Science-Metrix, personal communication, October 2018). In brief, the bibliometric indicators of CERC chairholders significantly exceed those of matched Tier 1 CRCs at each time point; with respect to the HCP10%, only CERCs showed an increase (albeit modest) from pre- to post-award.

Table 4: Key bibliometric indicators pre- and post-award for CERCs and CRC1s

| Program |

Pre-award |

Post-award |

Difference |

| ARC |

| CERC |

2.27 |

2.14 |

-0.13 |

| CRC1 (foreign) |

1.70 |

1.45 |

-0.25 |

| CRC1 (Canadian) |

1.73 |

1.82 |

0.09 |

| HCP 10% |

| CERC |

24.6% |

27.5% |

2.9% |

| CRC1 (foreign) |

20.9% |

18.8% |

-2.1% |

| CRC1 (Canadian) |

22.1% |

20.9% |

-1.2% |

| HCP 1% |

| CERC |

3.6% |

3.9% |

0.3% |

| CRC1 (foreign) |

2.2% |

0.4% |

-1.8% |

| CRC1 (Canadian) |

1.9% |

2.8% |

0.9% |

|

|

Source: Bibliometric analysis performed by Science-Metrix.

There are several potential explanations for the modest rather than pronounced increase in publication impact. The first is a possible ceiling effect—that is, in the pre-award period, CERC chairholders were already world-class researchers with high levels of funding. Additionally, as evidenced in the CERC evaluation conducted in 2013-14, there is typically a “recovery period” post-award whereby the logistics involved in building infrastructure and establishing a new team can take time away from research production. Relocating a full research program from one institution to another is a demanding endeavour, particularly when it involves moving to a new country. This transition requires, at the very least, building a new pool of undergraduate, master’s and doctoral students, as well as postdoctoral fellows; cementing relationships with potential new partners and collaborators; acquiring and calibrating instruments; and navigating a new set of administrative practices. The post-award figures presented in Table 4 encompass this recovery period, thus dampening the overall effect of post-award productivity. It is to be expected then that performance increases over the baseline would only be achieved after a longer time frame. As also evident in Table 4, a smoother transition is observed among matched Tier 1 Canadian CRCs who are not faced with as many logistical obstacles as CERCs and foreign CRCs in the immediate post-award period.

Another potential explanation for only modest increases in CERC publication impact as measured through bibliometric indicators is that, with their influx of funding, CERCs may be compelled to conduct overall riskier research that, in turn, might take more time to develop and cannot yet be captured by bibliometric analysis. A few faculty members participating in the CERC case studies confirmed that, indeed, the freedom and flexibility of CERC funding allowed them to pursue more challenging and higher-stakes research ventures than would have been possible otherwise. It has been found that riskier research typically takes more time both to be published and to be cited, although these initial delays are often contrasted by very strong citation profiles in the long term (Wang, Veugelers, & Stephan, 2015). Given that research projects can take years to complete, chairholders will likely experience (or continue to experience) an increase in CERC-related research outputs and outcomes following the completion of their terms.

It is important to bear in mind that publication volume is but one of many indices of research capacity and contributions. Moreover, as articulated in the limitations section of this document, we were only able to quantify the publication output of the CERC chairholder—we were not able to track the activity of the entire team. As such, the publication metrics reported here are likely underestimates of the actual increase in publication rates associated with CERC funding.

CERC chairholders have a positive impact on the productivity of host institutions

Host institutions produced a significantly greater number of annual publications in fields associated with the CERC relative to comparison groups. More specifically, host institutions experienced increases in publication output of roughly 10 articles per year above the trends of Canadian and international comparators, representing a 13.3% increase (see Figure 5). Importantly, this lead vanished if publications authored by CERC chairholders were removed from the institutional profiles. It was found, however, that these leads were driven by exceptional performances from a few CERC teams rather than by gains evenly distributed across the population of chairholders.

Figure 5: Average number of annual publications per year of host institutions with and without CERC articles and matched Canadian and foreign institutions

Host institutions saw significantly greater number of annual publications in fields associated with CERC relative to comparators

Source: Bibliometric analysis performed by Science-Metrix.

Figure 5 long description

Figure 5: Average number of annual publications per year of host institutions with and without CERC articles and matched Canadian and foreign institutions

Host institutions saw a significantly greater number of annual publications in fields associated with the CERC relative to comparators

|

Average papers per year |

| Host institutions |

92.1 |

| Host without CERC papers |

81.3 |

| Matched Canadian institutions |

82.8 |

| Matched foreign institutions |

81 |

Source: Bibliometric analysis performed by Science-Metrix.

4.2 Institutional growth

Summary of Findings: Evidence suggests that the CERC program has fostered institutional growth in a variety of ways, including through the addition of new infrastructure, programs and faculty.

One of the expectations of the CERC programs is that it will provide host institutions with the ability to grow, with institutional growth defined as an increase in the number of faculty, HQP, programs, facilities, and/or linkages with other institutions that would not otherwise have occurred had the CERC not been hosted at their institution. Overall, 96% of host institutions reported that CERCs were instrumental in stimulating institutional growth over the evaluation period. Interview and case study findings indicate that the CERCs have fostered institutional growth in a number of different ways, including by attracting a number of high-calibre faculty and HQP, enhancing existing research centres, building new infrastructure in CERC-supported research areas, supporting the establishment of research institutes and groups, allowing for leveraging of funding or support from other sources and helping to develop the international reputation of the host institution.

Regarding building new infrastructure in CERC-supported research areas, in total, CERC administrative data show that a median of $1 million of CERC funds were used to support infrastructure needs during the period covered by this evaluation. In addition, CERCs collectively received $12 million from CFI over this evaluation period (and a total of almost $24 million since the launch of the CERC program). Of note, there is wide variability in infrastructure-based spending of CERC funds across priority areas. The natural resources and energy priority area, for example, is associated with the highest infrastructure cost, with a minimum reported cost of nearly $550,000 in a given year (Mdn = $1.4 million). The second highest infrastructure cost is associated with the health priority area (Mdn = $1.3 million).

4.3 Collaborations and partnerships

Summary of Findings: Most CERC chairholders actively engage in national and international partnerships and collaborations, primarily with academic institutions: the vast majority of chairholders indicated that the CERC program has had a great influence on their ability to establish those partnerships and collaborations. The CERC program also offered partnership and collaboration opportunities for HQP, allowing them to build their professional networks to a degree that would not have been possible without the award.

The vast majority (over 80%) of chairholders agree that the CERC program, through its scale and calibre, had a great influence on their ability to establish partnerships and collaborations. Overall, 92% of CERCs reported engaging in partnerships and 82% reported engaging in international partnerships over the four-year period from 2014 to 2017, with a median of three partnerships reported in a given year. Overall, 96% of CERCs have reported engaging in both national and international collaborations over the same four-year period, with a median of four ongoing collaborations in a given year.

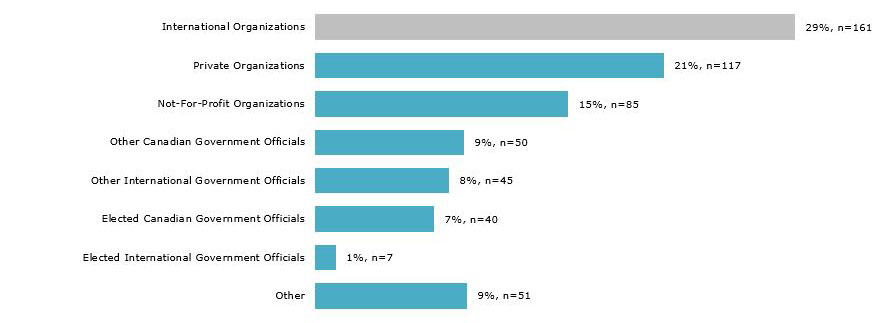

Case studies and key informant interviews underscored that their funding, reputation as chairholders and the quality of the research produced by their strong core team resulted in increased requests for media appearances, in addition to an influx of requests to deliver public lectures, attend international meetings, and explore professional relationships with groups and individuals they would not have otherwise had the opportunity to engage with. Moreover, access to financial and infrastructure resources through the CERC program allowed chairholders to leverage additional funding. According to administrative data, CERCs report a median amount of just under $1 million per year in external funding to support research endeavours, primarily from public organizations. Despite evidence of cross-sectoral collaborations and partnerships, Figure 6 clearly illustrates that CERCs partner and collaborate primarily with academic institutions; in particular, academic collaborators are almost four times more prevalent than collaborators from any other sector. This is not altogether surprising given the academic environment within which these teams operate.